Why Antiemetics Can Be Riskier Than You Think

Most people think of antiemetics as simple nausea pills-something you grab at the pharmacy after a bad stomach bug or chemo session. But these drugs aren’t harmless. Some can slow down your heart’s electrical rhythm in a way that could trigger a dangerous, even deadly, arrhythmia called torsades de pointes. Others make you so drowsy you can’t drive, work, or even hold a conversation. The real question isn’t whether they work-it’s whether they’re safe for you.

Let’s break it down. Antiemetics fall into several classes: serotonin blockers like ondansetron, dopamine blockers like haloperidol and metoclopramide, and newer agents like palonosetron and olanzapine. Each has different risks. Some are fine for healthy people. Others? Not so much.

QT Prolongation: The Silent Heart Risk

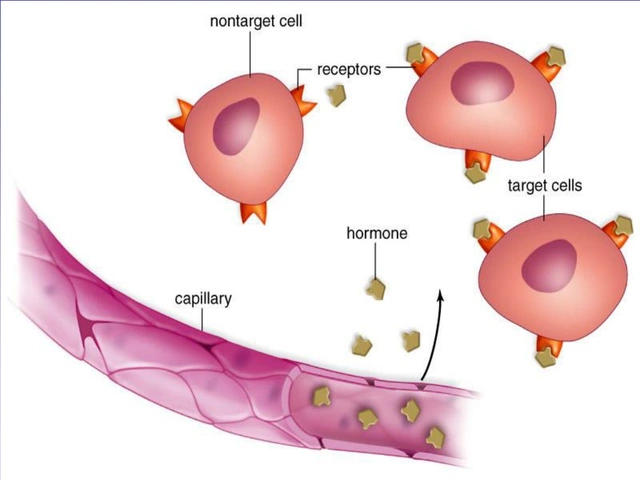

QT prolongation means your heart’s electrical cycle is taking longer than it should to reset after each beat. On an ECG, it shows up as a longer QT interval. When it gets too long-over 500 milliseconds or more than 25% above your baseline-it can spiral into torsades de pointes. This isn’t a theoretical risk. It’s been documented in emergency rooms and ICUs across the U.S.

Most antiemetics cause this by blocking the IKr potassium channel, which is essential for repolarization. Think of it like a traffic jam in your heart’s electrical system. When too many signals get backed up, the rhythm stutters-and sometimes stops.

Here’s the catch: QT prolongation doesn’t always mean danger. Many people have slightly longer QT intervals without any symptoms. But when you add other risk factors-low potassium, existing heart disease, or taking multiple QT-prolonging drugs-the risk jumps. In fact, 91% of documented cases of drug-induced QT prolongation involved patients on more than one such medication.

Ondansetron: The Most Common Culprit

Ondansetron is everywhere. It’s used in hospitals, ERs, and at home after chemotherapy. But it’s also the antiemetic most often linked to QT prolongation. A 2014 study in the Annals of Emergency Medicine found that a single 8 mg IV dose can stretch the QT interval by up to 20 milliseconds. That might sound small, but in vulnerable patients, it’s enough to tip the balance.

And here’s what most people don’t realize: oral ondansetron rarely causes this. The risk is almost entirely tied to intravenous use. So if you’re getting it as a pill or dissolving tablet, your risk is low. But if you’re in the hospital and getting an IV push, especially more than 8 mg, you’re in higher-risk territory.

Granisetron is similar-its IV form can prolong QT if given above 10 micrograms/kg. But palonosetron? It doesn’t. That’s why many clinicians now prefer palonosetron for patients with heart conditions or those on other heart-affecting drugs. It works better, lasts longer (up to 40 hours), and doesn’t mess with your heart rhythm.

Droperidol and Haloperidol: Overhyped Risks?

For years, droperidol was pulled from the market because of QT concerns. But recent data tells a different story. Studies like DORM-1 and DORM-2 showed no increase in torsades even at doses up to 20-30 mg. The same goes for haloperidol: at the typical antiemetic dose of 1 mg, the risk is minimal. The real danger comes with cumulative doses over 2 mg IV or when used with other QT-prolonging drugs.

So why the fear? Probably because droperidol’s label still carries a black box warning. But in practice, experienced providers use it safely every day-especially in the ER for severe nausea and vomiting. The key is avoiding it in patients with known long QT syndrome, electrolyte imbalances, or those already on multiple cardiac medications.

Phenothiazines and Metoclopramide: Sedation and Movement Risks

Promethazine and prochlorperazine are older, cheap, and effective. But they come with baggage. Promethazine is notorious for causing drowsiness-so much so that it’s sometimes used as a sleep aid. That’s fine if you’re at home. Not so great if you’re trying to get through a workday or care for a child.

Prochlorperazine? It’s less sedating, which makes it a better choice for people who need to stay alert. But it still carries some QT risk, especially at higher doses.

Metoclopramide is another story. It crosses the blood-brain barrier, which helps with nausea-but also causes muscle spasms, tremors, and even a rare condition called tardive dyskinesia. It also prolongs QT. That’s why it’s not first-line anymore, especially for older adults or those with Parkinson’s.

The New Players: Olanzapine and Domperidone

Olanzapine, originally an antipsychotic, has quietly become a go-to antiemetic for cancer patients. Why? Because it doesn’t prolong QT. It’s also less sedating than promethazine and works well for delayed nausea. The only downside? It’s not approved specifically for nausea in the U.S., so doctors prescribe it off-label.

Domperidone is another interesting option. It doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier, so it doesn’t cause drowsiness or movement disorders. But it can prolong QT-though only at very high doses. A 2021 study gave healthy volunteers up to 80 mg daily and found no QT changes. Still, caution is advised for older adults or those with liver problems.

Drowsiness: The Overlooked Side Effect

It’s easy to focus on heart risks and forget how many antiemetics make you feel like you’ve been hit by a truck. Promethazine? High sedation. Ondansetron? Usually fine. Palonosetron? Minimal drowsiness. Droperidol? Moderate. Olanzapine? Mild to moderate.

If you’re driving, operating machinery, or caring for someone who depends on you, drowsiness isn’t just inconvenient-it’s dangerous. And it’s often underreported. A 2023 EMCrit Project review flagged promethazine as a top offender, while prochlorperazine was rated as having “low concern about sedation.” That’s a big difference.

For elderly patients, drowsiness increases fall risk. For cancer patients, it adds to fatigue. For anyone with chronic illness, it can feel like the treatment is worse than the symptom.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone needs to avoid antiemetics. But if you fall into one of these groups, talk to your doctor before taking any:

- People with known long QT syndrome or family history of sudden cardiac death

- Those with low potassium, low magnesium, or kidney/liver disease

- Patients on multiple QT-prolonging drugs (antibiotics, antidepressants, antifungals)

- Older adults, especially over 65

- People with heart failure or previous arrhythmias

If you’re healthy, young, and taking a single oral dose of ondansetron? Your risk is very low. But if you’re 72, on diuretics, and getting IV ondansetron for chemo? That’s a different story.

What Should You Do?

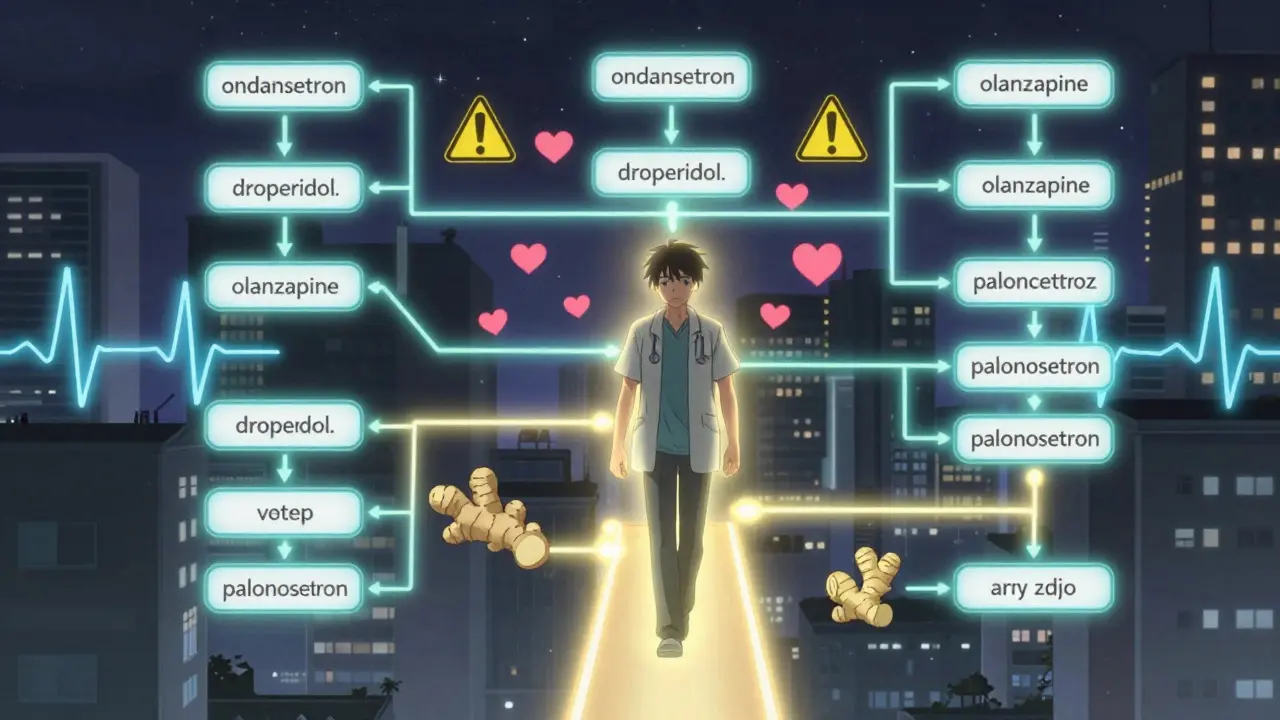

Here’s a simple decision tree:

- Are you at risk for QT prolongation? (Heart disease, electrolyte issues, multiple meds) → Avoid ondansetron and granisetron. Choose palonosetron or olanzapine.

- Do you need to stay alert? → Skip promethazine. Try prochlorperazine, palonosetron, or olanzapine.

- Are you elderly or have kidney problems? → Avoid metoclopramide. Domperidone may be safer, but only if liver function is normal.

- Is this for chemotherapy? → Palonosetron is the gold standard now. Better efficacy, no QT risk, longer action.

- Is this for post-op nausea? → Droperidol at 1 mg is safe and effective. Don’t fear it.

The bottom line: Antiemetics aren’t one-size-fits-all. What works for your cousin might not be safe for you. Always ask: “Is this the right drug for my body, not just my symptoms?”

When to Call Your Doctor

Stop the medication and get help immediately if you experience:

- Dizziness or lightheadedness that comes on suddenly

- Heart palpitations or skipped beats

- Fainting or near-fainting episodes

- Unusual muscle stiffness or spasms (especially with metoclopramide)

- Extreme drowsiness that doesn’t improve

These aren’t just side effects-they’re warning signs.

Can I take ondansetron if I have a history of heart problems?

If you have a history of heart rhythm issues, long QT syndrome, or are on other QT-prolonging medications, avoid IV ondansetron. Oral ondansetron at standard doses (4-8 mg) is lower risk but still requires caution. Palonosetron or olanzapine are safer alternatives. Always check your ECG and electrolytes before use.

Is domperidone safe in the U.S.?

Domperidone isn’t FDA-approved for nausea in the U.S. due to concerns about heart risks at high doses. However, it’s available through special access programs and compounding pharmacies. It’s often used off-label for breastfeeding mothers or patients who can’t tolerate other antiemetics. Use only under medical supervision, especially if you’re over 60 or have liver disease.

Why is palonosetron better than ondansetron?

Palonosetron lasts longer (up to 40 hours vs. 8 hours), works better for delayed nausea (common after chemo), and doesn’t prolong the QT interval-even at high doses. It’s also more effective than 8 mg of ondansetron, which is the standard dose many doctors still use. For cancer patients, it’s become the preferred first-line option.

Can I mix antiemetics with alcohol?

Never mix antiemetics with alcohol. Alcohol can worsen drowsiness, lower potassium levels, and increase the risk of QT prolongation. Even one drink with promethazine or metoclopramide can make you dangerously sleepy or dizzy. Avoid alcohol entirely while taking these drugs.

Are there non-drug options for nausea?

Yes. Ginger supplements, acupressure wristbands (like Sea-Bands), and small, frequent meals can help mild nausea. For chemotherapy patients, behavioral techniques like guided imagery or hypnosis have shown benefit. These aren’t replacements for severe cases, but they can reduce the need for drugs-and their risks.

Final Thoughts

Antiemetics save lives. But they’re not safe by default. The biggest mistake? Assuming all nausea meds are the same. Ondansetron isn’t just a “better version” of older drugs-it’s a different beast with different risks. Palonosetron, olanzapine, and even droperidol at low doses can be safer and more effective. The key is matching the drug to the patient, not the symptom.

If you’re prescribed an antiemetic, ask: “What’s the risk for me?” Your doctor should know. If they don’t, it’s time to ask for a second opinion. Because when it comes to your heart and your brain, you deserve more than a one-size-fits-all pill.

rasna saha

January 26, 2026 AT 11:21 AMI had chemo last year and they gave me ondansetron. I didn't think twice until my mom mentioned heart stuff. Turns out I had a weird ECG later and they switched me to palonosetron. So glad they did.

Stay safe out there, folks.

James Nicoll

January 27, 2026 AT 03:50 AMSo let me get this straight - we’re now treating nausea like it’s a hostage situation where the heart is the negotiator?

Next thing you know, we’ll need a waiver to take Pepto-Bismol.

John Wippler

January 28, 2026 AT 01:36 AMThis is the kind of post that makes me feel like I’m reading a medical thriller written by someone who actually survived the system.

People treat antiemetics like candy - pop one, no big deal. But the truth? It’s like choosing between a rusty ladder and a broken parachute. Ondansetron’s not evil - it’s just not for everyone.

Palonosetron? That’s the quiet hero in the back row. Doesn’t shout, doesn’t cause drama, just works. Olanzapine? The unapproved ninja.

And domperidone? The international fugitive with a heart of gold.

If you’re on multiple meds, old, or just plain tired of feeling like a lab rat - ask for the safer option. No shame. No guilt. Just smart.

Kipper Pickens

January 29, 2026 AT 21:49 PMThe pharmacokinetic profile of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists exhibits differential binding affinities and half-lives, which directly influence cardiac repolarization dynamics via IKr channel blockade. Ondansetron demonstrates dose-dependent QT prolongation primarily via IV administration due to bioavailability and peak plasma concentration kinetics. Palonosetron, with its higher receptor affinity and prolonged elimination half-life (up to 40 hours), demonstrates negligible IKr inhibition, thereby reducing torsades de pointes risk. This aligns with the 2020 ACC/AHA guidelines on drug-induced arrhythmias, which recommend avoiding high-dose IV 5-HT3 antagonists in patients with polypharmacy or baseline QTc >450ms.

Aurelie L.

January 30, 2026 AT 20:54 PMI took promethazine once. Slept for 14 hours. Woke up confused. My cat judged me.

Angie Thompson

February 1, 2026 AT 11:30 AMOMG this is so important!! 🙌 I’m a cancer caregiver and no one told me about the heart risks! I thought all nausea meds were the same 😭

Just switched my mom to palonosetron and she’s actually *alert* now!! 🥹💖

Also - ginger tea + Sea-Bands? Game changer. Not a replacement but SO helpful alongside meds.

Thanks for writing this. Someone should make a poster for ERs.

eric fert

February 1, 2026 AT 19:02 PMLet’s be real - this whole thing is fearmongering dressed up as medicine.

People die from falling out of bed. Should we ban beds?

QT prolongation? Yeah, it happens. But in 99.9% of cases, it’s just a number on a machine. You think your doctor doesn’t know this? They’ve seen more ECGs than you’ve had hot dinners.

And palonosetron? It’s expensive. So now we’re supposed to pay more so you can feel safe?

Meanwhile, real problems like opioid overdoses and sepsis get ignored because we’re too busy policing nausea pills.

Stop turning every drug into a villain. It’s not helping.

Curtis Younker

February 2, 2026 AT 00:45 AMI’m a nurse in oncology and I’ve seen this play out too many times.

One time, a 70-year-old woman got 16mg IV ondansetron for chemo nausea. She had diabetes, on diuretics, and was on amiodarone.

She coded 3 hours later. Torsades.

We saved her. But she was in ICU for a week.

It’s not paranoia. It’s pattern recognition.

Palonosetron costs more? Yes. But it saves money in the long run - no ICU stays, no code blues, no family trauma.

And olanzapine? I’ve watched patients who couldn’t eat for weeks start eating again after switching. No sedation. No tremors. Just relief.

Don’t be cheap with safety. Your body isn’t a budget spreadsheet.

Simran Kaur

February 2, 2026 AT 20:44 PMI’m from India and we use metoclopramide like it’s water. My aunt took it for months for nausea after her stroke. Then she started moving weird - like her face was doing a dance she didn’t control.

Turned out it was tardive dyskinesia.

Doctors said, 'It’s rare.' But rare doesn’t mean 'won’t happen to me.'

Thank you for writing this. My cousin is starting chemo. I’m printing this out and handing it to her doctor.

Neil Thorogood

February 3, 2026 AT 06:47 AMSo… I’m supposed to be afraid of a pill that stops me from puking?

Meanwhile, my cousin drinks 3 energy drinks a day, smokes, and takes Adderall… but we’re all scared of the nausea medicine?

Also, I’m pretty sure droperidol is the only thing that ever worked for my hangover nausea.

Maybe the problem isn’t the drug… it’s the fact that we treat medicine like a video game where every item has a hidden debuff? 😅

Jessica Knuteson

February 3, 2026 AT 07:04 AMQT prolongation is overblown

Robin Van Emous

February 4, 2026 AT 19:34 PMI appreciate the depth here. It’s rare to see a post that doesn’t just say 'avoid this drug' but actually helps you weigh trade-offs.

As someone with a family history of long QT, I’ve been scared to even take Advil sometimes. But this? This gives me a roadmap.

Thanks for not just listing risks - you showed me what to choose instead. That’s real care.

Skye Kooyman

February 5, 2026 AT 00:13 AMI read this while waiting for my chemo. Took a screenshot. Sent it to my mom. She cried.

Not because she’s scared. Because she finally understands why I keep asking, 'Is this the right one?'

Ashley Porter

February 5, 2026 AT 03:45 AMThe IKr blockade mechanism is well-documented across multiple antiemetic classes. However, the clinical significance is often confounded by comorbidities and polypharmacy. In isolation, most antiemetics pose minimal arrhythmic risk. The real concern lies in additive effects - particularly with macrolides, antifungals, and SSRIs. This is where risk stratification becomes essential.

Also, domperidone’s hepatic metabolism via CYP3A4 makes it problematic in liver impairment, regardless of QT data.