Steroid Psychosis Risk Assessment Tool

Risk Assessment

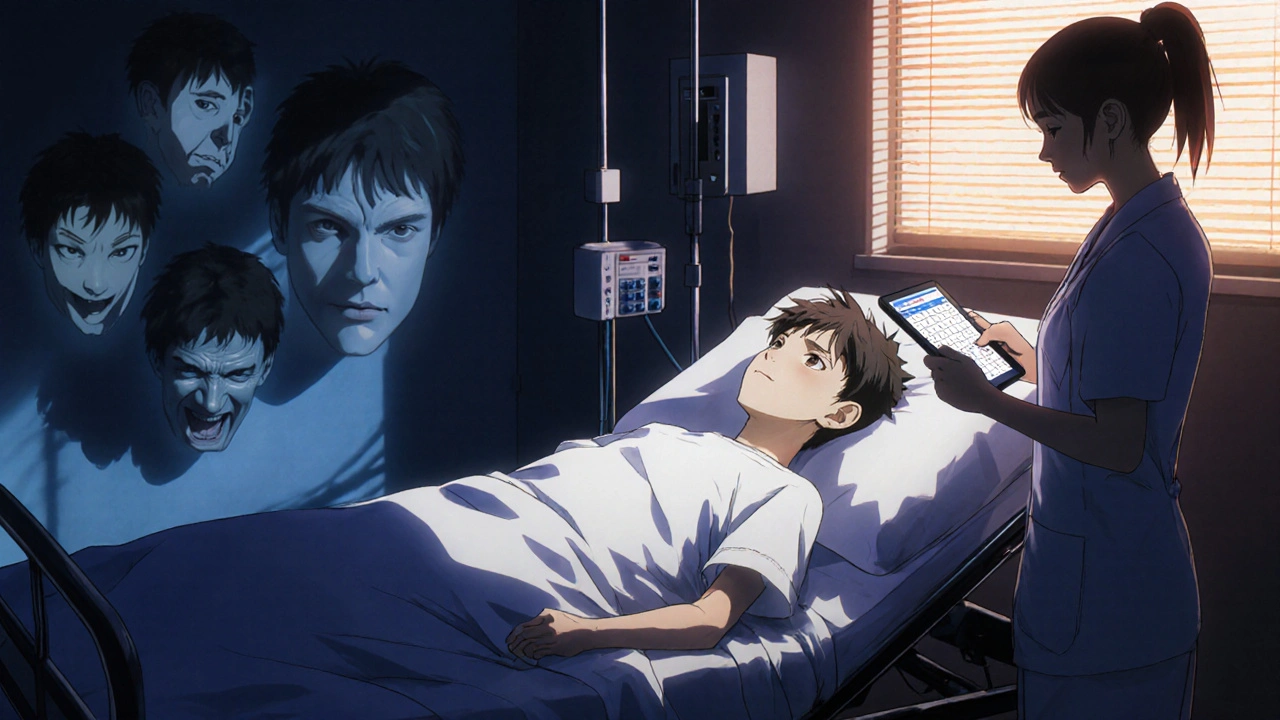

When someone starts taking high-dose steroids for asthma, lupus, or a flare-up of rheumatoid arthritis, they’re usually expecting relief - not hallucinations, paranoia, or violent outbursts. But steroid-induced psychosis is real, sudden, and dangerous. It doesn’t happen to everyone, but when it does, it can turn a routine treatment into a life-threatening crisis. Emergency teams see it more often than you’d think - and too often, it’s missed because no one connects the dots between the steroids and the behavior.

What Exactly Is Steroid-Induced Psychosis?

Steroid-induced psychosis is a psychiatric reaction triggered by corticosteroids like prednisone, dexamethasone, or methylprednisolone. It’s not a mental illness you were born with - it’s a side effect. The DSM-5 classifies it as a substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder. That means: hallucinations or delusions appear after steroid use, aren’t better explained by another condition like schizophrenia, and cause real harm - like losing your job, getting arrested, or trying to hurt yourself or others.

The numbers are startling. In hospitalized patients taking more than 80 mg of prednisone daily, nearly 1 in 5 develop serious psychiatric symptoms. Even at lower doses - say, 40 mg per day - about 1 in 20 people will show signs. These aren’t rare outliers. They’re predictable outcomes tied to dose and timing.

When Does It Start? The Critical Window

This isn’t something that creeps in over weeks. Symptoms usually hit fast - within the first 2 to 5 days after starting the steroid. Some patients report feeling "off" within hours. Early warning signs aren’t dramatic. They’re subtle: confusion, restlessness, irritability, trouble sleeping, or being overly suspicious. These are red flags, not just "bad days."

By day 5, if left unchecked, it can escalate into full-blown psychosis: hearing voices, believing people are plotting against you, acting aggressively, or becoming completely disoriented. In rare cases, patients try to jump out of windows or attack family members. Suicide risk spikes too. That’s why waiting for "clear signs" is deadly. By then, it’s already an emergency.

What Does It Look Like? Patterns in the Symptoms

Not everyone reacts the same way. Studies tracking hundreds of cases show clear patterns:

- 40% develop depression - feeling hopeless, crying constantly, refusing to eat

- 28% show mania - talking nonstop, spending recklessly, believing they’re invincible

- 14% have true psychosis - hallucinations, delusions, paranoia

- 10% experience delirium - confused, disoriented, not recognizing loved ones

Short-term steroid users (a few days to a week) are more likely to go manic. Long-term users (weeks or months) tend to crash into depression. But anyone can swing into psychosis, no matter the duration. And it doesn’t matter if they’ve never had mental health issues before. Steroids can trigger this in people with zero psychiatric history.

Why Does This Happen? The Science Behind the Madness

Steroids aren’t just anti-inflammatory drugs. They mimic cortisol - your body’s natural stress hormone. When you flood your system with synthetic versions, you throw off your brain’s delicate chemical balance. The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which normally keeps cortisol levels steady, gets suppressed. Your body stops making its own cortisol. That imbalance affects areas of the brain tied to mood, judgment, and perception - especially the prefrontal cortex and limbic system.

This is why steroid psychosis feels eerily similar to Cushing’s syndrome (too much natural cortisol) or even severe withdrawal from long-term use. The brain doesn’t know the difference between your body’s cortisol and the drug version. It just knows: too much, too fast. And when that happens, neurons misfire. Thoughts become distorted. Reality slips away.

Emergency Response: What to Do Right Now

If someone on steroids suddenly becomes paranoid, aggressive, or delusional, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s "just stress." Treat it like a medical emergency.

- Ensure safety first. Remove sharp objects. Keep others away. Don’t try to reason with someone in full psychosis - it won’t work. Calm, low voices help, but physical safety comes before conversation.

- Check the steroid history. Ask: What steroid? What dose? When did they start? Did they recently increase it? If it’s over 40 mg prednisone daily, the risk is high.

- Rule out mimics. High blood sugar, low sodium, infections like UTI or pneumonia, or even a brain tumor can look like psychosis. Get labs: glucose, electrolytes, CBC, cortisol levels, and a urine drug screen.

- Start treatment fast. If the patient is calm enough to swallow pills, give low-dose antipsychotics: olanzapine 2.5-5 mg, risperidone 1-2 mg, or haloperidol 0.5-1 mg. These aren’t for "crazy people" - they’re for correcting a chemical imbalance caused by the steroid.

- Don’t overmedicate. Many ER doctors give 20-30 mg of olanzapine, thinking more is better. That’s wrong. Steroid psychosis responds to much lower doses than schizophrenia. High doses cause sedation, low blood pressure, or even dangerous movement disorders.

If the patient is violent or uncooperative, use IM olanzapine (10 mg) or IM haloperidol (2-5 mg) with lorazepam (1-2 mg) if needed. Avoid restraints unless absolutely necessary - they can make psychosis worse and cause physical injury.

The Real Fix: Tapering the Steroid

Medications help calm symptoms - but they don’t fix the root cause. The only way to truly reverse steroid-induced psychosis is to reduce the steroid dose.

Here’s the key: 92% of patients fully recover once the dose drops below 40 mg prednisone daily. That’s not a guess - it’s from multiple clinical studies. You don’t always need to stop steroids completely. You just need to go lower.

But tapering isn’t simple. If someone is on steroids for a life-threatening condition - like a transplant rejection or severe autoimmune disease - dropping the dose too fast can be deadly. That’s why this needs to be done with input from both the prescribing doctor and a psychiatrist. The goal isn’t to stop the steroid - it’s to find the lowest effective dose that doesn’t trigger psychosis.

What If You Can’t Taper?

Sometimes, the underlying disease demands high-dose steroids. In those cases, you can’t stop. But you still need to treat the psychosis.

Long-term antipsychotics become necessary. Olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol are the most studied. Lithium can help prevent mania, but it’s risky - it affects kidneys and thyroid, and requires constant blood tests. Antidepressants like SSRIs might help if depression dominates. Some doctors use mood stabilizers like valproate or carbamazepine, but evidence is weaker.

There’s no FDA-approved drug for this specific condition. That doesn’t mean nothing works. It just means doctors have to use what’s available - carefully.

Why Do So Many Miss It?

A 2022 survey of emergency doctors found that while 89% knew steroids could cause psychosis, only 43% followed the recommended tapering protocol. Why? Three reasons:

- They assume the patient has a pre-existing mental illness

- They think psychosis means "schizophrenia," not a drug side effect

- They’re afraid of tapering steroids and causing a medical crisis

That’s dangerous thinking. Steroid psychosis is one of the most treatable forms of psychosis - if caught early. Delaying treatment doesn’t just prolong suffering. It increases the chance of hospitalization, legal trouble, or suicide.

What’s Next? Better Tools Coming

Researchers are working on ways to predict who’s at risk before it happens. The NIH is tracking 500 patients on high-dose steroids, looking for genetic markers or blood biomarkers that signal rising psychosis risk. Early results suggest certain gene variants make people more sensitive to steroid effects on the brain.

By mid-2025, the American Psychiatric Association plans to release a clinical decision tool that will help doctors input a patient’s age, steroid dose, medical history, and early symptoms - then spit out a risk score and recommended action. This could turn steroid psychosis from an emergency into a preventable event.

Final Takeaway: Don’t Ignore the Subtle Signs

Steroid-induced psychosis isn’t rare. It’s underrecognized. If someone on steroids suddenly seems "not themselves," act. Ask: "When did they start the steroids?" "What’s the dose?" "Have they had mood changes?"

Low-dose antipsychotics work. Tapering works. Waiting doesn’t. The goal isn’t to scare people away from steroids - they save lives. But every dose carries risk. And knowing how to spot and respond to psychosis can mean the difference between recovery and tragedy.

Justin Daniel

November 24, 2025 AT 06:54 AMI’ve seen this happen to my uncle on high-dose prednisone after his transplant. He thought the TV was talking to him. We thought he was going crazy… turns out it was the meds. Took 3 days to taper down and he was back to normal. Doctors need to warn people before they hand out these pills like candy.

Melvina Zelee

November 25, 2025 AT 05:00 AMso like… steroids make you hallucinate?? no wonder my cousin thought her dog was a spy. she was on 60mg for lupus and started yelling at the cat like it was plotting to steal her soul. lol. but also… not lol. this is real. why isn’t this on the pill bottle??

steve o'connor

November 27, 2025 AT 01:34 AMThis is spot on. I’m an ER nurse in Dublin and we see this way more than people realize. One guy thought his IV drip was a drone. We gave him 2.5mg olanzapine and he just… blinked. Said, 'Wait, why is the nurse wearing a hat made of fire?' Then he laughed. Pure relief. Tapering’s the key.

ann smith

November 27, 2025 AT 12:38 PMThis is such an important post. 🙏 Many patients are terrified of steroids, but they save lives. The key is awareness. If you or a loved one is on high-dose steroids and suddenly seems 'off,' please speak up. Early intervention = full recovery. You’re not overreacting - you’re being a hero. 💙

Julie Pulvino

November 27, 2025 AT 12:51 PMI had a friend on 80mg for RA who started screaming at her mirror because she thought her reflection was mocking her. She didn’t have a history of mental illness. The ER doc just gave her Xanax and sent her home. She ended up in psych after a week. This needs to be common knowledge. Not just for docs - for patients too.

Patrick Marsh

November 28, 2025 AT 18:09 PMDon’t wait.

Robin Johnson

November 29, 2025 AT 14:42 PMIf you’re on steroids and feel like you’re losing your mind - you probably are. Don’t blame yourself. Don’t wait for someone else to notice. Tell your doctor immediately. Low-dose antipsychotics work fast. Tapering works faster. This isn’t weakness. It’s biology. And it’s fixable.

Latonya Elarms-Radford

November 30, 2025 AT 05:06 AMAh, the modern paradox: we weaponize cortisol to save lives, only to unravel the very fabric of consciousness in the process. It’s almost poetic - a chemical echo of Prometheus, stealing fire from the gods, only to burn oneself. We treat inflammation with a substance that inflames the soul. The mind, that fragile cathedral of neural architecture, collapses under the weight of synthetic mimicry. Are we healing… or just trading one hell for another? 🌑

Mark Williams

December 1, 2025 AT 06:53 AMHPA axis dysregulation + glucocorticoid receptor hypersensitivity in limbic regions → aberrant glutamatergic signaling → cortical disinhibition. That’s the neuropharmacological cascade. Olanzapine’s 5-HT2A/D2 antagonism mitigates this, but the real win is dose reduction. Biomarkers like FKBP5 expression are being validated for predictive risk stratification - upcoming APA tool will integrate this.

Daniel Jean-Baptiste

December 1, 2025 AT 14:39 PMmy bro got on steroids for a bad flare and started thinkin he was the president. he tried to 'negotiate peace' with the mailman. we got him to the hospital and they cut his dose and gave him a tiny bit of risperidone. he was fine in 48 hrs. why dont drs tell people this? its crazy.

Shawn Daughhetee

December 1, 2025 AT 22:09 PMmy aunt went from zero to screaming at the walls in 3 days on prednisone. no one believed us till she tried to drive to the hospital because she thought the neighbors were poisoning her with microwaves. they gave her 5mg olanzapine and she cried and said 'i just wanted to sleep'... we all need to know this

Miruna Alexandru

December 3, 2025 AT 07:13 AMThe irony is that this condition is entirely iatrogenic - a direct consequence of medical intervention - yet it is routinely pathologized as if the patient were inherently unstable. The failure to recognize steroid-induced psychosis as a pharmacological side effect, rather than a psychiatric failure, reflects a deeper epistemological bias in clinical practice: the tendency to attribute behavioral change to internal pathology rather than external chemical influence.

Danny Nicholls

December 4, 2025 AT 06:04 AMthis is so real 😭 my cousin was on 120mg for a bad flare and started thinking her phone was alive. she’d whisper to it like it was her therapist. we took her to the ER, they dropped her dose and gave her 2.5mg olanzapine. she was back to normal in 2 days. why isn’t this taught in med school?? 🤦♂️

Michael Fitzpatrick

December 4, 2025 AT 23:17 PMI’ve been on long-term steroids for Crohn’s for 8 years. I’ve had three episodes of this - one where I thought my dog was a government agent, another where I believed I was being filmed by satellites. I’ve learned to monitor myself. If I’m irritable for more than 2 days, I call my doc. Tapering by 5mg at a time saved me from hospitalization twice. This isn’t rare. It’s just hidden. We need more awareness - not just in ERs, but in primary care. And patients need to be trained to recognize their own red flags. You’re not crazy. You’re just medicated.

luke young

December 5, 2025 AT 17:52 PMThis is the kind of post that should be mandatory reading for every person getting prescribed steroids. I’m so glad someone laid it out like this. No fluff. Just facts. Thank you.