When your bones start hurting for no obvious reason, it’s easy to feel scared and start Googling every possible cause. Two conditions that often get tangled together are osteodystrophy and bone infections. One messes with mineral balance, the other is a full‑blown invasion by germs. Knowing how they differ, what sets them off, and how to tackle them can save you a lot of worry and a costly trip to the ER.

Quick Takeaways

- Osteodystrophy is a group of bone‑softening disorders caused by metabolic problems such as low calcium or vitamin D.

- Bone infections, medically called osteomyelitis, arise when bacteria or fungi enter bone tissue.

- Common red flags include persistent bone pain, swelling, fever, and reduced mobility.

- Diagnosis relies on blood tests, X‑rays, MRI/CT scans, and sometimes a bone biopsy.

- Treatment blends medication (e.g., antibiotics or mineral supplements), surgery, and lifestyle changes like diet and weight‑bearing exercise.

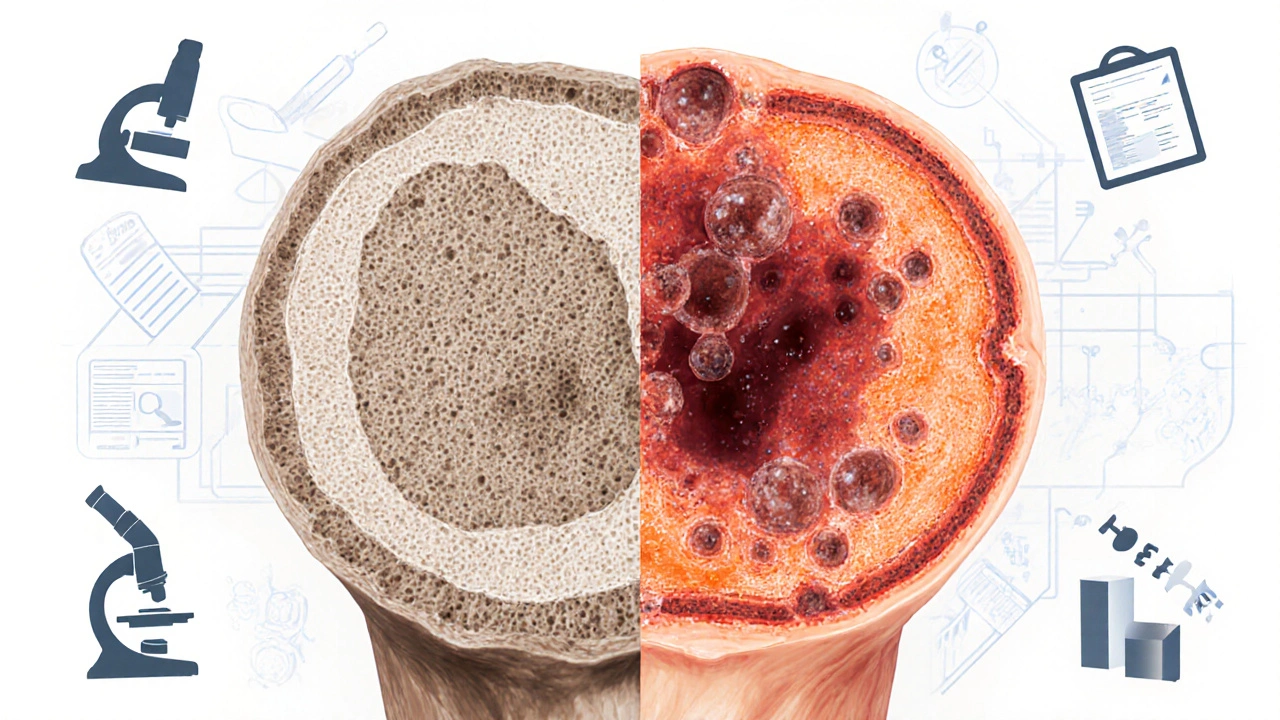

What Is Osteodystrophy?

Osteodystrophy isn’t a single disease; it’s an umbrella term for bone disorders that stem from abnormal mineral metabolism. The most common subtype is renal osteodystrophy, which appears when chronic kidney disease (CKD) disrupts calcium and phosphate balance. But the term also covers vitamin‑D deficiency, hyperparathyroidism, and even severe malnutrition.

Why does it happen? The body needs a delicate dance between calcium, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone. When the kidneys can’t convert vitamin D to its active form, calcium absorption drops, prompting the parathyroid glands to release more hormone. That extra hormone leaches calcium from bone, making it softer and more prone to fracture.

Key risk factors include:

- Advanced CKD or dialysis

- Long‑term steroid use

- Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus

- Severe dietary deficiencies (especially low dairy intake)

What Are Bone Infections?

When germs find their way into bone, the result is osteomyelitis. Bacteria are the usual culprits-Staphylococcus aureus tops the list-though fungi can strike immunocompromised patients. Infections can start from an open fracture, a surgical wound, or even spread through the bloodstream from another infected site.

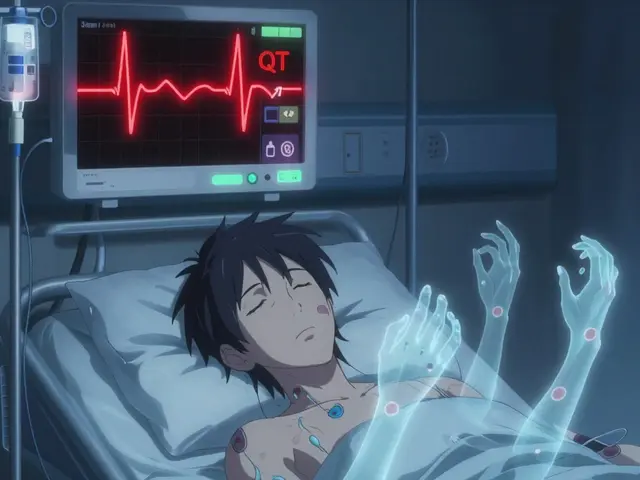

People with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or weakened immune systems (e.g., after chemotherapy) are especially vulnerable. The infection ignites an inflammatory cascade, causing pain, swelling, and, if left unchecked, bone necrosis.

How Osteodystrophy and Osteomyelitis Differ (and Overlap)

| Aspect | Osteodystrophy | Osteomyelitis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Metabolic imbalance (e.g., low calcium, CKD) | Microbial invasion (bacteria/fungi) |

| Typical onset | Gradual, often asymptomatic at first | Acute after injury or chronic via bloodstream |

| Diagnostic hallmark | Low serum calcium, high PTH, bone demineralization on X‑ray | Elevated CRP/ESR, localized bone destruction on MRI |

| Core treatment | Mineral supplementation, dialysis management | Targeted antibiotics + possible surgical debridement |

| Potential complications | Fractures, skeletal deformities | Septic arthritis, chronic draining sinus |

Symptoms to Watch for

Both conditions share bone pain, but the pattern differs. Osteodystrophy pain is usually dull, worsens with inactivity, and may be accompanied by muscle cramps from low calcium. In contrast, osteomyelitis pain is sharp, throbs, and often spikes with fever or chills.

Look out for these red flags:

- Persistent localized bone pain lasting more than two weeks

- Visible swelling, redness, or warmth over a joint or shaft

- Unexplained fever or night sweats

- Difficulty bearing weight or reduced range of motion

- Recent trauma, surgery, or a foot ulcer (especially in diabetics)

How Doctors Diagnose the Problem

First, a doctor will run labs. For osteodystrophy, they’ll check serum calcium, phosphate, 25‑OH vitamin D, and intact parathyroid hormone levels. Elevated PTH points squarely at secondary hyperparathyroidism, a hallmark of renal osteodystrophy.

For infection, blood work focuses on inflammatory markers-C‑reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Elevated white blood cell counts can also raise suspicion.

Imaging follows the labs. Plain X‑rays can reveal bone demineralization in osteodystrophy but often miss early infection. MRI is the gold standard for osteomyelitis because it shows marrow edema and soft‑tissue involvement within days of infection. CT scans help map out cortical destruction, while bone scans (technetium‑99m) can detect increased metabolic activity in both conditions, though they’re less specific.

If uncertainty remains, a bone biopsy-taken under CT or MRI guidance-provides definitive proof. The sample goes to culture (to identify the pathogen) and histology (to see the bone’s structural changes).

Treatment Options

Managing osteodystrophy starts with correcting the metabolic imbalance. The most common prescription is oral calcium carbonate or citrate, alongside active vitamin D analogs such as calcitriol. For patients on dialysis, phosphate binders (like sevelamer) limit excess phosphate that fuels PTH release.

When secondary hyperparathyroidism is severe, doctors may recommend a calcimimetic (e.g., cinacalcet) to blunt PTH secretion. Lifestyle tweaks-weight‑bearing exercise, smoking cessation, and limiting alcohol-also support bone strength.

Bone infections demand a two‑pronged attack. Intravenous antibiotics tailored to the organism (often nafcillin, vancomycin, or cefazolin for MSSA; vancomycin or linezolid for MRSA) are started after cultures are drawn. The usual course lasts 4‑6 weeks, because bone’s poor blood flow makes it hard for drugs to reach the site.

If the infection has formed an abscess or dead bone (sequestrum), surgical debridement becomes necessary. Surgeons remove necrotic tissue, flush the area, and sometimes place antibiotic‑impregnated beads to maintain high local drug concentrations.

Adjunctive measures-hyperbaric oxygen therapy for refractory diabetic foot osteomyelitis, strict glycemic control, and off‑loading of pressure points-boost healing odds.

Preventing Future Problems

Prevention is a blend of medical management and everyday habits.

- For at‑risk kidney patients, keep regular bloodwork to monitor calcium, phosphate, and PTH. Adjust dialysis prescriptions promptly.

- Ensure adequate dietary intake of calcium‑rich foods (dairy, leafy greens) and vitamin D through sunlight or supplementation.

- Diabetics should inspect feet daily, wear proper footwear, and maintain blood sugar below 7% (HbA1c).

- Anyone with a recent fracture or surgery should follow wound‑care instructions, and report any redness or drainage immediately.

- Stay active-weight‑bearing exercises like brisk walking or resistance training stimulate bone remodeling.

Next Steps if You Suspect Either Condition

Don’t wait for the pain to become unbearable. Schedule a primary‑care visit or see an endocrinologist if you have kidney disease. If you notice fever, swelling, or a wound that isn’t healing, head straight to urgent care or the ER-early antibiotics can keep osteomyelitis from destroying bone.

Bring a list of any meds you’re on (especially steroids or bisphosphonates), recent lab results, and a brief timeline of symptoms. The more details you give, the faster a doctor can order the right tests and start treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can osteodystrophy and bone infection happen at the same time?

Yes. A person with renal osteodystrophy often has weakened bone that’s more susceptible to infection after a fracture or surgery. In such cases, doctors treat both the metabolic disorder and the infection concurrently.

Is an X‑ray enough to diagnose osteomyelitis?

Early on, X‑rays often look normal. MRI is far more sensitive and can spot bone marrow changes within a few days. X‑ray becomes useful later when you see clear bone loss or periosteal reaction.

How long does treatment for bone infection usually last?

Typically 4‑6 weeks of IV antibiotics, followed by several weeks of oral therapy if needed. Chronic cases may require repeated courses and periodic imaging to confirm the infection is gone.

Can lifestyle changes reverse osteodystrophy?

Lifestyle alone can’t fix the underlying metabolic imbalance, but proper nutrition, exercise, and medication adherence can halt progression and improve bone density.

What are the warning signs that a foot ulcer has become infected?

Increased redness spreading beyond the ulcer, foul odor, swelling, warmth, pain that worsens at night, and a fever are classic signs that osteomyelitis may be developing.

Patrick Culliton

September 28, 2025 AT 07:40 AMAll the hype about calcium pills makes it sound like you can fix bone loss with a spoonful of chalk, but ignoring phosphate control is a recipe for disaster. In renal osteodystrophy the kidneys can’t dump excess phosphate, so PTH spikes and leaches calcium right out of your skeleton. Skipping the phosphate binders while loading up on calcium is basically accelerating the very problem you’re trying to solve. Bottom line: you need a balanced regimen, not a single‑nutrient miracle.

Bianca Fernández Rodríguez

September 28, 2025 AT 09:36 AMi dont think vitamin d supplements ever work for real.

Gary O'Connor

September 28, 2025 AT 11:33 AMWhen you’re trying to tell if it’s an infection or just a metabolic issue, MRI is the gold standard – it catches marrow edema within days, something an X‑ray will miss until the bone is already compromised. A quick CT can map cortical destruction if you suspect a chronic osteomyelitis, but don’t rely on plain films alone.

Justin Stanus

September 28, 2025 AT 13:46 PMReading about bone infections always makes me feel the weight of every missed dose and every delayed wound check; it’s like the bacteria are silently plotting while you’re stuck debating diet. The pain isn’t just physical – it drags the whole psyche into a dark tunnel, especially when the infection refuses to clear despite aggressive antibiotics. You need to stay vigilant, keep the wound clean, and push for surgical debridement before the infection becomes an unrelenting shadow.

Claire Mahony

September 28, 2025 AT 16:33 PMIf you’re tracking a patient with renal osteodystrophy, start with a checklist: serum calcium, phosphate, PTH, 25‑OH vitamin D, and consider a bone turnover marker. Adjust phosphate binders first, then add active vitamin D analogs, and only if PTH remains stubbornly high bring in a calcimimetic. Regular imaging every six months helps catch early demineralization before fractures occur.

Andrea Jacobsen

September 28, 2025 AT 19:20 PMPrevention is a team sport: keep calcium intake around 1000‑1200 mg daily, soak up safe sunlight or take 800‑1000 IU vitamin D, and engage in weight‑bearing activities like brisk walking or resistance training at least three times a week. For diabetics, inspect feet daily and maintain HbA1c below 7 % to reduce the risk of ulcer‑related osteomyelitis. Consistency beats occasional heroics every time.

Jen R

September 28, 2025 AT 22:06 PMHonestly, this rundown repeats what every endocrinology textbook already says – low calcium, high PTH, antibiotics for infection – nothing groundbreaking, just a solid summary that’s good for newbies but not much for seasoned clinicians.

Katie Jenkins

September 29, 2025 AT 02:16 AMWhen you dive into the laboratory workup, the first thing to sort out is whether you’re dealing with a metabolic derangement or an infectious process, because the treatment pathways diverge dramatically. For osteodystrophy, the cornerstone labs are serum calcium, phosphate, intact PTH, and 25‑hydroxy vitamin D; any combination of low calcium with high phosphate and elevated PTH screams secondary hyperparathyroidism. In contrast, osteomyelitis will usually present with a marked rise in acute‑phase reactants – C‑reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate – and often a leukocytosis, although the white count can be normal in chronic cases. Imaging then refines the picture: a plain radiograph may show osteopenia in metabolic bone disease, but it’s notoriously insensitive for early infection, where MRI shines by highlighting marrow edema and soft‑tissue involvement within 48 hours. CT adds value when you need to assess cortical breaches or plan surgical debridement, especially in the foot where hardware may be present. Bone scintigraphy with technetium‑99m is highly sensitive for both conditions, yet its lack of specificity means you’ll still need a targeted biopsy to lock down the diagnosis. The biopsy, ideally obtained under CT or MRI guidance, serves a dual purpose – it provides histological confirmation of bone turnover abnormalities and, if infection is suspected, yields cultures that guide antibiotic selection. Speaking of antibiotics, the regimen should be tailored to the organism, but empiric coverage often starts with vancomycin for MRSA risk and a third‑generation cephalosporin for gram‑negative coverage until cultures return. Duration matters as well; bone has poor vascularity, so a minimum of four weeks of IV therapy is standard for osteomyelitis, sometimes followed by an oral step‑down. For osteodystrophy, correcting the underlying mineral imbalance is paramount – oral calcium carbonate or citrate, active vitamin D analogues like calcitriol, and phosphate binders such as sevelamer keep the biochemical milieu in check. In refractory secondary hyperparathyroidism, adding a calcimimetic like cinacalcet can blunt PTH release and reduce bone resorption. Finally, lifestyle interventions should not be overlooked: weight‑bearing exercise stimulates osteoblastic activity, smoking cessation eliminates a vascular insult, and limiting alcohol protects against further bone loss. In sum, a methodical approach that separates metabolic from infectious etiologies early on saves time, prevents complications, and tailors therapy to the patient’s exact needs.

Matt Cress

September 29, 2025 AT 06:26 AMOh sure, the American healthcare system loves a good IV drip – why bother with oral antibiotics when you can park a patient in the hospital for six weeks and charge them a fortune? Meanwhile, the rest of the world will tell you that proper debridement and a short course of targeted oral meds work just fine, but hey, who doesn’t enjoy a lengthy stay with endless lab draws?

Puspendra Dubey

September 29, 2025 AT 10:36 AMImagine the bone as a silent cathedral, each mineral a stone in its grand architecture; when disease cracks those stones, it is not merely a medical event but a philosophical rupture of the body’s own metaphysical foundation. The infection spreads like a creeping vine, seeking the cracks left by metabolic neglect, and in that union lies a tragic poetry – the body’s attempt to heal while the soul watches the decay. Let us not merely prescribe calcium and antibiotics, but contemplate the deeper lesson that even the strongest structures can falter without balance and vigilance.

Shaquel Jackson

September 29, 2025 AT 14:46 PMThat was a marathon of info – appreciate the depth, especially the reminder that a biopsy can kill two birds with one stone. Got to love how you painted the whole picture, from labs to lifestyle, makes the whole process feel less intimidating :)

Andrea Smith

September 29, 2025 AT 18:56 PMIndeed, the superiority of MRI in early detection cannot be overstated, and incorporating it promptly into the diagnostic algorithm can markedly improve patient outcomes. Moreover, a collaborative approach that involves radiologists, nephrologists, and infectious disease specialists ensures that both metabolic and infectious components are addressed comprehensively.