When a patient takes a pill that combines two or more drugs - like a blood pressure medication with a diuretic, or an asthma inhaler with both a steroid and a bronchodilator - they expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But getting a generic version of these combination products to market isn’t as simple as copying a single-drug pill. The science behind proving they’re equivalent - called bioequivalence - is far more complex, and it’s holding back affordable alternatives for millions of patients.

Why Combination Products Are Harder to Copy

Most generic drugs are straightforward: take a single active ingredient, match its absorption in the body, and you’re done. But combination products? They’re a puzzle. A fixed-dose combination (FDC) - like metformin and sitagliptin for diabetes - contains two active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in one tablet. Each drug has its own solubility, absorption rate, and metabolism path. When you mix them, they can interfere with each other. One might slow down the other’s absorption. Or the tablet’s coating might protect one ingredient but not the other. This means a generic version might look identical on the outside but behave completely differently inside the body. The FDA requires generic makers to prove bioequivalence not just to the brand-name combination product, but also to each individual drug taken separately. That’s not a one-test job. It often means running three-way crossover studies where volunteers take the brand product, the generic, and the two drugs taken alone - in random order - over weeks. Each time, blood samples are drawn to measure how much of each drug enters the bloodstream. The data must show that the generic delivers both drugs within 80-125% of the brand’s levels. If one drug fails, the whole product fails - even if the other works perfectly.Topical Products: Can You Measure What Doesn’t Show Up in Blood?

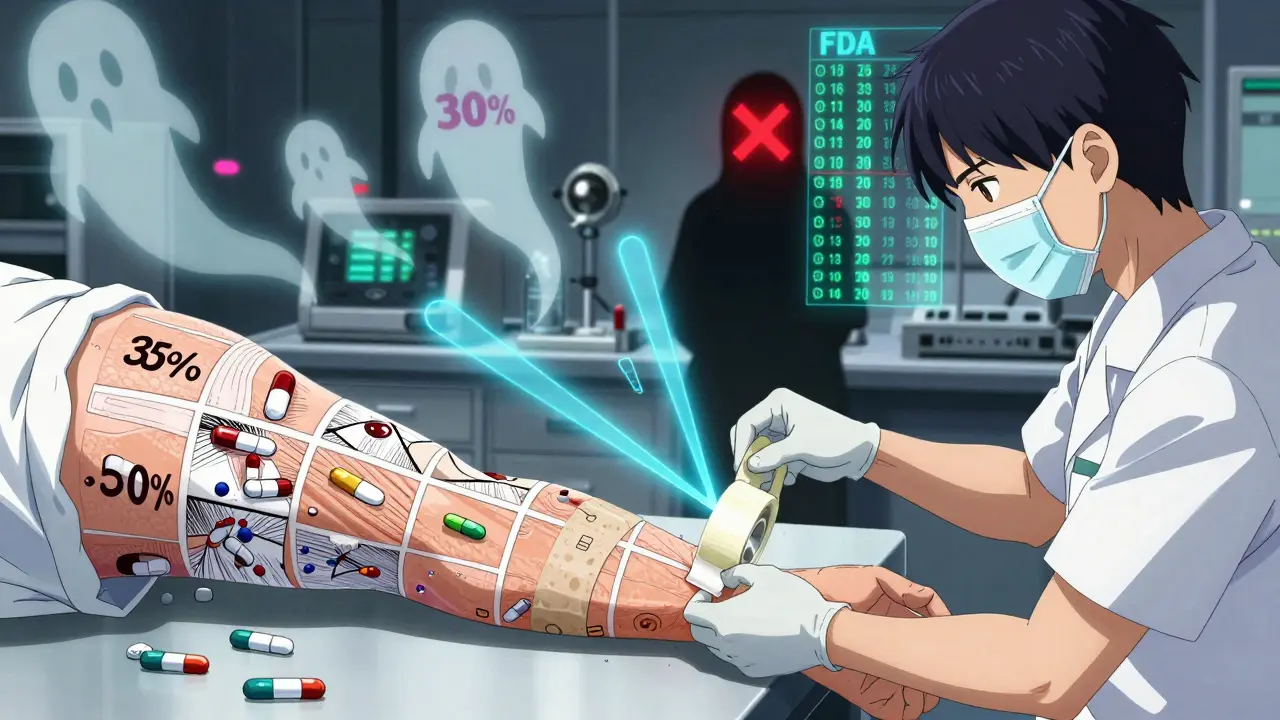

For creams, ointments, or foams applied to the skin - like those used for eczema or psoriasis - measuring bioequivalence gets even trickier. These drugs don’t enter the bloodstream in significant amounts. Instead, they need to reach the top layer of skin, the stratum corneum. But how do you prove a generic cream delivers the same amount as the brand? The FDA currently relies on tape-stripping: sticking adhesive strips to the skin, peeling them off, and measuring how much drug is pulled out. But here’s the problem: there’s no standard on how many strips to use, how deep to go, or how much skin to analyze. One lab might take 15 strips; another might take 20. The results vary wildly. A 2024 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology showed that even slight differences in technique led to 30% variation in drug measurements. That’s why some generic developers have spent years trying to get approval - and failed three times in a row. One company spent over $8 million trying to get a generic version of calcipotriene/betamethasone foam approved. Each study failed because the drug penetration numbers didn’t match the brand’s.

Drug-Device Combos: It’s Not Just the Medicine - It’s the Delivery

Inhalers, auto-injectors, and nasal sprays are another category entirely. These aren’t just pills or creams - they’re machines that deliver medicine. A generic inhaler might contain the exact same drug as the brand, but if the nozzle shape, button pressure, or propellant flow is even slightly different, the particle size of the aerosol changes. And that changes where the drug lands in the lungs. The FDA requires that generic inhalers deliver 80-120% of the reference product’s aerodynamic particle size distribution. But testing this isn’t easy. It requires expensive equipment, controlled labs, and trained technicians. A 2024 FDA workshop revealed that 65% of complete response letters - the official notice that a generic application is rejected - cite problems with device performance, not drug content. One generic manufacturer told investors that their inhaler submission failed because the device’s actuation force was 5% higher than the brand. That small difference meant fewer particles reached the deep lung.Costs and Delays: Why Fewer Generics Are Coming to Market

Developing a generic single-drug product typically costs $1-3 million and takes 2-3 years. For combination products? It’s $15-25 million and 4-6 years. Bioequivalence studies alone can eat up 40% of that budget. Labs need liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) machines - each costing $300,000-$500,000 - and scientists trained for years to run them. The FDA’s own data shows that complex product applications take 38.2 months for first-cycle approval, compared to just 14.5 months for standard generics. And the failure rate? It’s brutal. For modified-release FDCs - like extended-release diabetes or pain meds - 35-40% of initial applications are rejected because bioequivalence wasn’t proven. Teva Pharmaceuticals reported that 42% of their complex product failures were due to bioequivalence issues. Mylan (now Viatris) said development timelines for topical products stretched by 18-24 months. Small companies can’t afford this. Many have simply walked away.

How the Industry Is Trying to Fix This

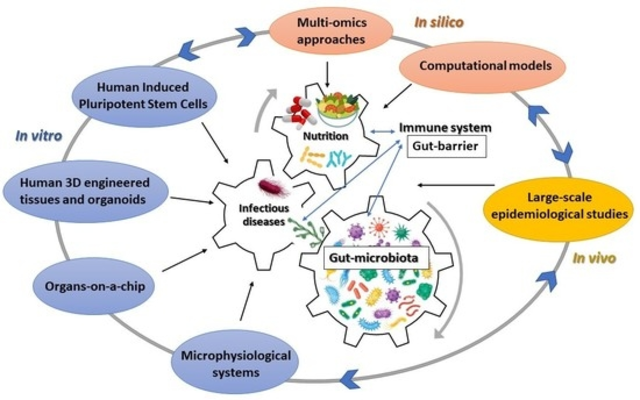

The FDA isn’t ignoring the problem. Since 2021, they’ve launched the Complex Generic Products Initiative, and by 2024, they’d released 12 product-specific bioequivalence guidances. These aren’t general rules - they’re tailored for specific drugs. For example, a new guidance for a combination HIV drug (dolutegravir/lamivudine) now requires simultaneous bioequivalence testing of both components with tighter statistical limits. Some companies are turning to modeling. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling simulates how drugs behave in the body using computer algorithms. The FDA has accepted this method in 17 approved generics since 2020. One case study from Simulations Plus showed PBPK modeling cut clinical testing by 40% - saving millions and years of development time. The FDA is also working with NIST (the National Institute of Standards and Technology) to create reference materials for inhalers and topical products. These aren’t drugs - they’re calibrated standards that labs can use to ensure their measurements are accurate. The first standards for inhalers are expected by late 2024. That’s a big deal. Right now, two labs testing the same product might get different answers. With reference standards, they’ll all be speaking the same language.What’s Next? The Road to Faster Access

The global market for complex generics hit $112.7 billion in 2023. But only a fraction of these products have generic alternatives. The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance promises 15 more product-specific rules by the end of the year, with a goal of 50 new guidances by 2027. The focus? Respiratory products - where 78% of submissions currently fail bioequivalence testing. In vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is another promising tool. Instead of waiting for human trials, labs are testing how a cream releases drug in a dish - and using that to predict how it will behave on skin. A 2024 pilot study showed 85% accuracy in predicting real-world performance. If this scales, it could cut development time for topical products by half. The bottom line? Bioequivalence for combination products isn’t just science - it’s a bottleneck. Until regulators, industry, and labs align on standardized methods, patients will keep paying more for drugs that could - and should - be cheaper. The technology exists. The data is there. What’s missing is consistency.Why can’t generic manufacturers just copy the brand-name combination product exactly?

Because combination products aren’t just mixtures of drugs - they’re complex systems. The way the ingredients are formulated, coated, or delivered can change how each drug is absorbed. Even small changes in manufacturing - like a different binder or particle size - can alter the drug’s behavior in the body. Copying the ingredients isn’t enough; you have to copy the entire system, and proving that requires advanced testing.

Do bioequivalence requirements differ between the FDA and EMA for combination products?

Yes. The FDA often accepts advanced methods like PBPK modeling or in vitro testing for complex products. The EMA, however, still requires more clinical data in many cases - especially for topical and inhalation products. This means companies often have to run separate studies for each market, increasing costs by 15-20% and delaying entry.

What’s the biggest reason generic combination products fail approval?

The biggest reason is inconsistent bioequivalence data - especially for multi-component products. For FDCs, if one drug meets the 80-125% range but the other doesn’t, the whole application fails. For drug-device products, device performance issues - like differences in inhaler actuation or spray pattern - account for 65% of rejections. Lack of standardized testing methods is the root cause.

Can PBPK modeling replace human bioequivalence studies for combination products?

In some cases, yes. The FDA has approved 17 generic applications using PBPK modeling since 2020. It works best when there’s strong prior data on how the drug behaves in the body. For complex products with multiple APIs, PBPK can reduce the need for clinical trials by 30-50%. But it’s not a replacement for all studies - regulators still require some human data, especially for new delivery systems or narrow therapeutic index drugs.

Why are small generic companies hit harder by these challenges?

Because developing a generic combination product can cost $15-25 million and take 5+ years. Small companies don’t have the capital, labs, or regulatory teams to handle multiple failed attempts. A single bioequivalence study failure can wipe out a company’s budget. The 2023 survey by the Complex Generic Consensus Group found 89% of small and mid-sized firms consider current requirements “unreasonably challenging.”

Will new reference standards from NIST help solve these problems?

Yes - significantly. Right now, different labs get different results testing the same product because there’s no common standard. NIST’s reference materials will let labs calibrate their instruments to the same baseline. For inhalers and topical products, this could cut variability by 50% or more, making testing more reliable and reducing failed submissions.