What Parkinson’s Disease Really Does to Your Body

When you hear the word Parkinson’s disease, you might picture a trembling hand. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Parkinson’s is a slow, creeping change in how your brain controls movement - and it affects far more than just shaking. It starts quietly, often with a slight stiffness in one arm or a reduction in your usual arm swing while walking. Over time, simple things like getting out of bed, buttoning a shirt, or speaking clearly become harder. The root cause? A steady loss of dopamine-producing neurons in a small area of the brain called the substantia nigra. Without enough dopamine, your brain struggles to send clear signals to your muscles. This isn’t just aging. It’s a neurological shift that changes your daily life.

The Four Core Motor Symptoms

Doctors don’t diagnose Parkinson’s based on one symptom. They look for a pattern. The four key motor signs are tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Not everyone has all of them at first, but one is always present: bradykinesia. That’s the medical term for slowness of movement. It doesn’t mean you’re tired. It means your brain can’t trigger movements quickly enough. You might notice you blink less, your face looks expressionless, or you take longer to get dressed. Studies show it can take over three times longer to button a shirt compared to someone without Parkinson’s.

Tremor is what most people recognize - the pill-rolling motion between thumb and finger. It happens when you’re resting, not moving. About 70% of people notice it first in one hand, and it fades when they reach for a cup or pick up a phone. But here’s the surprise: 20-30% of people with Parkinson’s never have tremor at all. That’s why bradykinesia is the true diagnostic anchor.

Rigidity feels like stiffness in your limbs, like moving through thick syrup. Some people describe it as a ratchet effect - cogwheel rigidity - where your arm catches and releases as someone moves it. Others feel constant resistance, like lead pipe. About 85% of patients experience the ratchet type. This stiffness isn’t just annoying; it makes turning in bed or standing up from a chair harder.

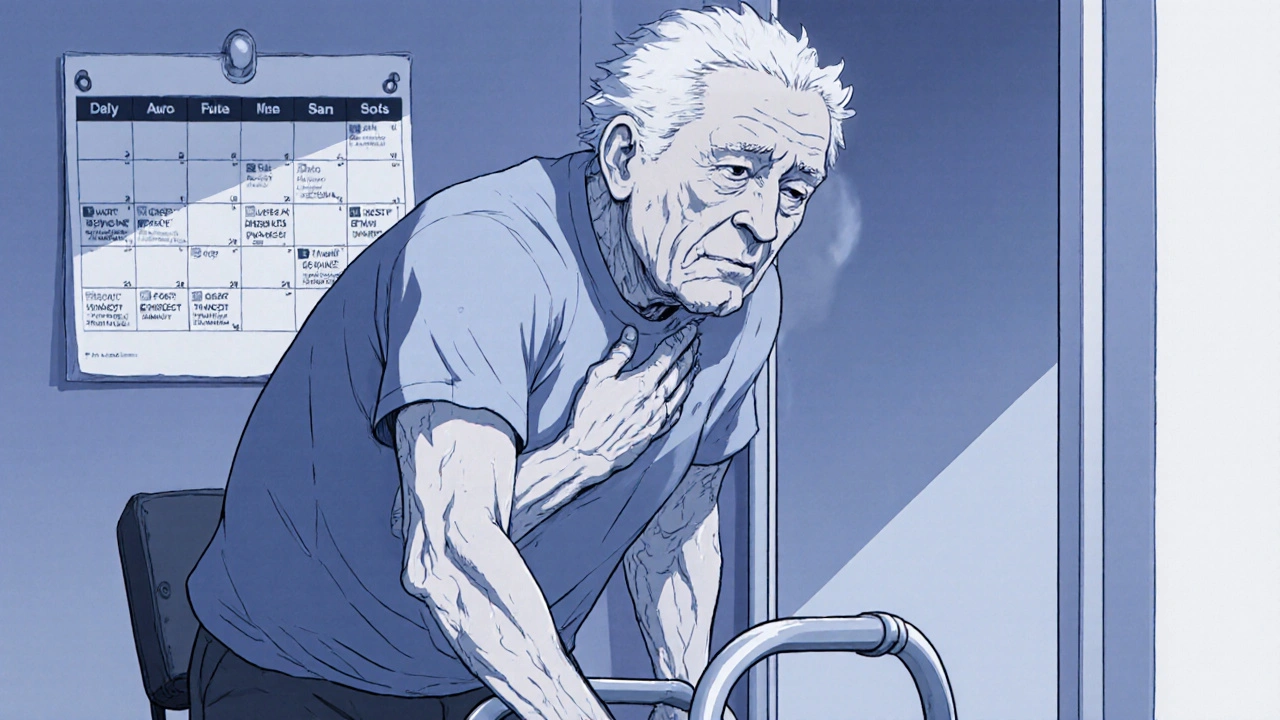

Postural instability comes later - usually after five to ten years. It’s not just being unsteady. It’s your body’s balance system breaking down. You might lean forward, stumble when turning, or fall without warning. About 68% of people with Parkinson’s fall at least once a year. Falls are the leading cause of injury and hospitalization.

Other Motor Signs You Might Not Notice

Beyond the big four, Parkinson’s brings a quiet storm of smaller changes. Your voice gets softer - often by 5 to 10 decibels - making conversations in noisy rooms a struggle. About 89% of people develop hypophonia. Speech can also become slurred, or dysarthric, affecting 74%. You might not realize your words are harder to understand until someone says, “I can’t hear you.”

Handwriting shrinks. Micrographia - writing that gets smaller and more cramped - happens in nearly half of patients. You might think you’re just writing faster, but the lines get tighter, the letters overlap. It’s your brain losing fine motor control.

Swallowing changes too. You might drool because you’re not swallowing as often as you used to. Or you might choke on food or liquids. Dysphagia affects 35-80% of people depending on how far the disease has progressed. That’s not just inconvenient - it raises the risk of pneumonia, which causes 70% of Parkinson’s-related deaths.

Arm swing disappears. You walk with stiff arms, not swinging naturally. That’s not just a quirk - it throws off your balance. Studies show 75% of people lose this motion, making turns and uneven ground more dangerous.

How Medications Work - and Where They Fall Short

There’s no cure for Parkinson’s. But there are medications that help you live better for longer. The gold standard is levodopa. It’s a chemical your brain turns into dopamine. Since the 1960s, it’s been the most effective tool we have. About 70-80% of people see big improvements in movement when they start it. But it’s not perfect.

After five years, about half of people begin to experience motor fluctuations. One minute, they move well. The next, they’re frozen. This is called “on-off” cycling. And then there’s dyskinesia - involuntary, wriggling movements that happen when levodopa levels are too high. It’s a side effect of success. The drug works too well, and your brain can’t regulate it.

That’s why younger patients (under 60) often start with dopamine agonists like pramipexole or ropinirole. These mimic dopamine without turning into it. They’re less likely to cause dyskinesia early on, but they’re not as strong. They help about half of early-stage patients. They can also cause dizziness, sleepiness, or impulse control issues - like gambling or overeating.

For people who’ve been on levodopa for a decade or more, and whose symptoms are no longer controlled by pills, deep brain stimulation (DBS) becomes an option. It’s surgery. Electrodes are placed in the brain to send electrical pulses that block faulty signals. About 30% of long-term patients eventually get DBS. It doesn’t stop the disease, but it can give back hours of good movement each day.

How Daily Life Changes - And How to Adapt

Imagine trying to get dressed when your fingers won’t cooperate. Or walking down the hall when your feet feel glued to the floor. That’s daily life with Parkinson’s. Simple tasks become physical puzzles.

Turning over in bed? Hard. About 65% of people struggle with this within five years. Getting out of a chair? Requires planning. You can’t just push up - you need to lean forward, shift weight, then stand. Many people use chairs with arms, or even raise their seats with cushions.

Walking gets slower. Step length drops by 25-35%. Speed drops by 30-40%. You take shorter, shuffling steps. That’s why falls happen. But exercise can help. Twelve weeks of targeted physical therapy - focusing on balance, strength, and big movements - improves walking speed by 15-20% and cuts fall risk by 30%. Tai chi, dance, and boxing programs designed for Parkinson’s have proven results.

Speech therapy helps too. Techniques like the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD) train people to speak louder and clearer. Many report being heard again after just four weeks of daily practice.

Even eating changes. Soft foods, thickened liquids, and timed swallowing exercises can reduce choking risk. A speech-language pathologist can guide you through this.

What Doesn’t Work - And What to Avoid

There are no magic supplements, no miracle diets, no essential oils that reverse Parkinson’s. The science is clear: nothing on the market slows the disease. Research is ongoing - especially around alpha-synuclein, the protein that clumps in Parkinson’s brains - but no treatment has yet shown disease-modifying power in large trials.

Don’t waste money on unproven therapies. Don’t believe claims that “natural” remedies can cure you. Parkinson’s isn’t caused by toxins or stress - it’s a neurological degeneration. You can’t out-eat it. You can’t out-supplement it.

But you can out-train it. Movement is medicine. So is social connection. Isolation makes depression worse, and depression is common in Parkinson’s. Stay active. Join a support group. Talk to others who get it.

Progression and What to Expect

Parkinson’s moves slowly. It doesn’t strike like a stroke. It creeps. The Hoehn and Yahr scale breaks it into five stages:

- One side of the body affected - mild symptoms, no daily disruption

- Both sides affected - balance still okay, but tasks take longer

- Mild to moderate balance problems - falls possible, but still independent

- Significant disability - needs help with daily tasks, can still walk

- Wheelchair-bound or bedridden - requires full-time care

Most people stay in stages 1-3 for many years. Only about 15% reach stage 5 within 10 years. The goal isn’t to stop progression - it’s to live fully within it.

Why Early Diagnosis Matters

Diagnosing Parkinson’s early isn’t about curing it. It’s about managing it before it takes too much. The earlier you start physical therapy, the more mobility you keep. The earlier you adjust your home - grab bars, non-slip mats, raised toilet seats - the safer you stay. The earlier you talk to a neurologist about medication timing, the better your symptom control.

Bradykinesia is the key. If you’re slowing down - in movement, speech, or even thinking - and it’s new, get checked. Don’t assume it’s just aging. A neurologist can spot the subtle signs: reduced blink rate, small handwriting, stiff arms, a soft voice. They can rule out mimics like essential tremor or normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Living Well with Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s changes your body. But it doesn’t have to change your spirit. People with Parkinson’s still travel, cook, garden, and laugh. They adapt. They use voice assistants to control lights. They wear magnetic buttons instead of zippers. They set alarms to remind themselves to swallow. They find joy in what they can still do.

The truth is, Parkinson’s isn’t just a disease of movement. It’s a disease of adaptation. And with the right tools - medication, therapy, community - you can keep living well for a long time.

Can Parkinson’s be cured?

No, there is currently no cure for Parkinson’s disease. Treatments like levodopa and deep brain stimulation help manage symptoms and improve quality of life, but they don’t stop the underlying brain cell loss. Research into disease-modifying therapies - especially those targeting alpha-synuclein - is ongoing, but none have proven effective in large clinical trials yet.

Is tremor always the first sign of Parkinson’s?

No. While tremor is the most common symptom at diagnosis - appearing in about 70% of cases - 20-30% of people never experience it. The one symptom that’s always present is bradykinesia, or slowness of movement. This includes reduced facial expression, slower walking, difficulty with fine tasks like buttoning clothes, and decreased blinking. Doctors rely on bradykinesia as the core diagnostic feature.

How long can someone live with Parkinson’s?

Most people with Parkinson’s live for many years after diagnosis, often 10 to 20 years or more. The disease itself isn’t fatal, but complications like pneumonia from swallowing difficulties, falls, or infections can be. With good management - including physical therapy, proper nutrition, and medication timing - many people maintain independence and a good quality of life well into their 80s and beyond.

What’s the best exercise for Parkinson’s?

The best exercise is the one you’ll stick with. But research shows that programs focusing on large, forceful movements work best. Tai chi improves balance. Boxing training (like Rock Steady Boxing) boosts strength and coordination. Dance, especially tango, helps with rhythm and posture. Even brisk walking, done regularly, can improve step length and reduce fall risk. Aim for at least 2.5 hours per week. Physical therapy tailored to Parkinson’s can make a big difference - studies show a 15-20% improvement in walking speed after 12 weeks.

Does levodopa stop working over time?

It doesn’t stop working - but the brain’s ability to handle it changes. After 5 to 10 years, many people start having “on-off” periods where medication effects wear off quickly between doses. They may also develop dyskinesia - uncontrolled movements - when the drug peaks. This isn’t a failure of the drug; it’s a sign the brain is losing its ability to regulate dopamine levels. Doctors adjust dosing schedules, add other medications, or consider deep brain stimulation to manage these changes.

Can diet help with Parkinson’s symptoms?

Diet won’t slow Parkinson’s, but it can help manage symptoms. High-protein meals can interfere with levodopa absorption, so some people spread protein intake evenly throughout the day or take medication 30-60 minutes before meals. Staying hydrated and eating fiber-rich foods helps with constipation, a common non-motor symptom. Soft, easy-to-swallow foods reduce choking risk if dysphagia is present. There’s no “Parkinson’s diet,” but smart eating supports overall health and medication effectiveness.

When should someone consider deep brain stimulation (DBS)?

DBS is typically considered when medications no longer provide consistent symptom control - usually after 10 years or more of living with Parkinson’s. Signs include frequent “off” periods, severe dyskinesia, or tremor that doesn’t respond well to drugs. It’s not for everyone. Candidates must be in good general health, have a clear diagnosis, and respond well to levodopa. A neurologist and neurosurgeon team evaluate each case. DBS doesn’t cure Parkinson’s, but it can restore several hours of good mobility each day.

Bonnie Youn

November 30, 2025 AT 23:27 PMI don't care what the studies say - if you move your body hard enough, Parkinson's doesn't win. I've seen people in their 70s boxing 3x a week and laughing like they're 30. Don't sit still. Don't accept limits. Move. Now.

And stop wasting money on snake oil supplements. The only thing that matters is sweat.

Edward Hyde

December 1, 2025 AT 17:41 PMThis post reads like a pharmaceutical brochure with extra steps. Levodopa? DBS? Please. The real cause is glyphosate in your oat milk and 5G brain rot. They don't want you to know the truth because Big Pharma profits from keeping you dependent. I’ve been researching this for 12 years. The data’s buried.

Karandeep Singh

December 2, 2025 AT 08:56 AMtremor not always first sign? really? i thought it was the thing everyone knows about parkinsons

Rachel Stanton

December 3, 2025 AT 20:34 PMLet me clarify something important: bradykinesia isn’t just slowness - it’s motor initiation failure. The basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit is dysregulated due to dopaminergic depletion. That’s why cueing strategies (auditory, visual, tactile) are so effective - they bypass the faulty internal trigger.

Physical therapy isn’t optional. It’s neuroplasticity engineering.

Debbie Naquin

December 5, 2025 AT 06:18 AMDopamine is just the messenger. The real question is why the neurons die. Is it mitochondrial dysfunction? Alpha-synuclein prion-like propagation? Or is the body’s immune system turning against itself? We treat the symptom, not the silence behind it.

Lauryn Smith

December 5, 2025 AT 13:58 PMI know someone who started with tiny handwriting and barely noticed. Then one day she couldn’t button her coat. It wasn’t sadness. It was physics. Her brain stopped talking to her fingers.

But she started dancing. Every Tuesday. Now she laughs louder than ever. It’s not a cure. It’s a rebellion.

Charlotte Collins

December 5, 2025 AT 18:17 PMThe article is technically accurate but emotionally sanitized. No one talks about the shame of drooling in public. Or how your spouse has to remind you to swallow. Or how your voice fades until you’re screaming into the void just to be heard.

This isn’t a medical textbook. It’s a slow erasure.

Scotia Corley

December 6, 2025 AT 23:35 PMOne must approach this condition with intellectual rigor. The notion that exercise can 'out-train' neurodegeneration is not only scientifically misleading but potentially dangerous. While motor adaptation may occur, the underlying pathology progresses inexorably. One must not confuse compensation with cure.

Mary Ngo

December 8, 2025 AT 18:13 PMI’ve read every study. I’ve met every specialist. And I still think this is all a lie. Parkinson’s isn’t neurological. It’s a targeted bioweapon. The same labs that developed mRNA tech are now selling levodopa. Why do you think the symptoms match so perfectly with early 2000s neurotoxin trials?

They want you docile. They want you dependent. They want you to believe in pills.

Kenny Leow

December 9, 2025 AT 21:16 PMIn my country, we don’t call it Parkinson’s. We call it 'the quiet storm'. Because it doesn’t roar - it just takes things, one small thing at a time.

My uncle danced until he couldn’t. Then he started humming. Then he stopped humming. Now we sit together in silence. He still knows my name. That’s enough.

Suzanne Mollaneda Padin

December 10, 2025 AT 23:39 PMI work with a speech therapist who uses LSVT LOUD. One patient went from whispering to leading church choir again. It’s not magic. It’s repetition. Muscle memory. Voice is the last thing people notice they’ve lost. And the first thing they fight to get back.

Erin Nemo

December 12, 2025 AT 03:38 AMI just started noticing my handwriting got tiny. Thought I was rushing. Went to the doc. Turned out it was early stage. I’m 52. Scared. But I joined a boxing class. First time in years I felt strong. Not cured. Just not done yet.

James Allen

December 13, 2025 AT 16:22 PMI love how Americans treat this like a workout challenge. 'Out-train it'? Bro. In other countries, we don’t turn disease into a motivational poster. We hold hands. We sit. We cry. We don’t need to 'beat' it. We need to be seen.

elizabeth muzichuk

December 15, 2025 AT 01:03 AMI lost my husband to this. They told him to 'stay active'. He did. He fought. He cried himself to sleep every night because he couldn’t hug his grandkids without shaking.

And now you want me to believe exercise is the answer?

Where was the cure? Where was the help? They sold him hope and took his dignity.