When a generic drug hits the market, you assume it works just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know for sure? For simple pills, checking peak concentration (Cmax) and total drug exposure (AUC) used to be enough. But for complex formulations-like extended-release opioids, slow-release heart medications, or abuse-deterrent painkillers-those old metrics often miss the real differences that could mean the difference between safe treatment and dangerous side effects. That’s where partial AUC comes in.

Why Traditional Bioequivalence Metrics Fall Short

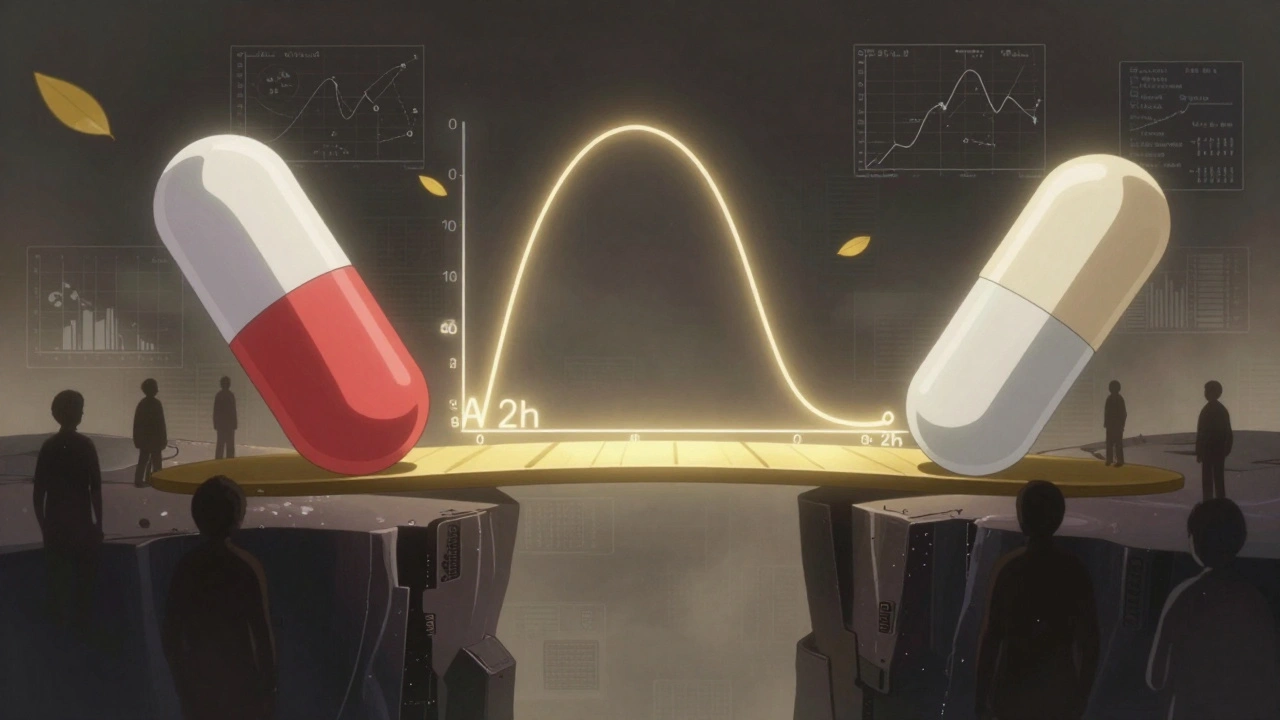

For decades, bioequivalence studies relied on two numbers: Cmax (the highest concentration in the blood) and total AUC (the total drug exposure over time). If the generic drug’s Cmax and AUC fell within 80-125% of the brand-name drug’s, regulators approved it. Simple. Clean. But for drugs designed to release slowly, or in multiple phases, this approach was blind to critical differences. Take an extended-release painkiller. The brand version might release 30% of its dose in the first hour, then trickle out the rest over 12 hours. A generic might have the same total exposure-but release 50% in the first hour. That’s a problem. Too much early release could lead to overdose risk. Too little could mean no pain relief. Cmax and total AUC wouldn’t catch it. The shape of the curve mattered, but the old metrics couldn’t see it. This wasn’t just theoretical. In 2014, a study in the European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences found that 20% of generic drugs that passed traditional bioequivalence tests failed when partial AUC was applied. When researchers looked at both fasting and fed conditions together, failure rates jumped to 40%. That meant nearly half the generics approved under old rules might not behave the same way in real patients.What Is Partial AUC (pAUC)?

Partial AUC is a targeted measurement. Instead of looking at the entire drug concentration curve from zero to infinity, it zooms in on a specific time window-usually the early absorption phase-where differences in drug release matter most. Think of it like checking only the first 30 minutes of a marathon, not the whole race. If two runners start at different speeds, you’ll notice it right away. The same logic applies to drugs. The FDA and EMA define pAUC as the area under the concentration-time curve between two time points: a start time (usually zero) and an end time tied to a clinically meaningful event. That end time might be:- The time when the reference drug reaches its peak concentration (Tmax)

- When drug levels hit 50% of Cmax

- Or when concentrations drop below a threshold linked to therapeutic effect

How pAUC Is Calculated and Analyzed

Calculating pAUC isn’t just cutting a piece of the curve. It’s a statistical process with strict rules. The FDA recommends using the natural logarithm of pAUC values, then comparing the test and reference products using analysis of variance (ANOVA)-just like with Cmax and AUC. The 80-125% bioequivalence range still applies. But here’s the catch: pAUC is more variable. Because you’re focusing on a narrow window, small measurement errors or individual differences in absorption can inflate the numbers. That means studies often need bigger sample sizes. One Teva biostatistician reported that switching to pAUC for an extended-release opioid generic increased their study size from 36 to 50 subjects-adding $350,000 to development costs. Statistical methods like the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller confidence interval are often used, especially in destructive sampling studies (where each subject only gives one blood sample). This approach accounts for the fact that not every subject provides a full concentration-time profile. The FDA’s 2017 Quantitative Modeling Workshop made it clear: pAUC should be sensitive to differences where drug levels are high, and ignore noise where levels are low. That’s why the cutoff time matters so much. If you pick the wrong window, you might miss a real difference-or flag a harmless one.

When Is pAUC Required?

pAUC isn’t needed for every generic drug. It’s reserved for products where traditional metrics are inadequate. The FDA’s product-specific guidances (PSGs) now list over 127 drugs requiring pAUC analysis as of 2023. These fall mostly into these categories:- Extended-release formulations (e.g., metformin ER, oxycodone ER)

- Abuse-deterrent opioids (e.g., Embeda, OxyContin)

- Mixed-mode products (e.g., immediate-release + extended-release combos)

- Modified-release CNS drugs (e.g., antidepressants, antiepileptics)

- Cardiovascular drugs with narrow therapeutic windows (e.g., diltiazem ER)

Real-World Impact: Preventing Dangerous Generics

pAUC isn’t just a regulatory checkbox. It’s saved lives. At the 2021 AAPS meeting, a case study showed how pAUC caught a 22% difference in early exposure between a test and reference product that traditional metrics missed. That difference would have gone unnoticed. The generic was pulled before it reached patients. Without pAUC, it might have been approved-and patients could have experienced rapid spikes in drug levels, leading to toxicity. Another example: abuse-deterrent opioids. Before pAUC, some generics mimicked the total release profile but were easy to crush and snort. pAUC forced manufacturers to match the early release pattern, making the generic as hard to abuse as the brand. That’s not just science-it’s public health.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite its value, pAUC isn’t easy. One major complaint from generic drug developers is the lack of standardization. FDA guidances vary in how they define the time window. Only 42% of product-specific guidances clearly explain how to pick the cutoff time. That creates uncertainty. One company might use Tmax of the reference product. Another might use 50% of Cmax. Both are valid-but they’re not interchangeable. In 2022, the FDA rejected 17 ANDA submissions because of incorrect pAUC time intervals. That’s 8.5% of all bioequivalence-related deficiencies that year. There’s also a cost issue. A 2022 survey by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 63% of companies needed extra statistical help for pAUC-compared to just 22% for traditional metrics. Smaller firms often outsource this work to specialized CROs like Algorithme Pharma, which now control 18% of the complex generic bioequivalence market. Dr. Donald Mager from the University at Buffalo noted that pAUC can require 25-40% larger sample sizes. That means longer studies, higher costs, and slower approvals. For a small generic company, that’s a barrier.What’s Next for pAUC?

The trend is clear: pAUC is becoming standard. In 2015, only 5% of new generic submissions included pAUC. By 2022, that jumped to 35%. Evaluate Pharma predicts that by 2027, 55% of all generic approvals will require it. The FDA is working on solutions. In January 2023, they launched a pilot program using machine learning to automatically determine optimal pAUC time intervals based on reference product data. This could cut down subjectivity and improve consistency. The IQ Consortium reports that inconsistent pAUC rules across countries add 12-18 months to global drug development. Harmonizing standards-especially between the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada-is the next big challenge. But the science is solid. As the FDA’s 2021 white paper put it: "The principles and rationales for using pAUCs are scientifically sound and necessary to ensure therapeutic equivalence for certain drug products where traditional metrics fall short."What You Need to Know

If you’re a patient: you don’t need to understand pAUC to take your medication. But you should know that regulators now have a better tool to make sure your generic drug behaves just like the brand. That’s not marketing-it’s science. If you’re in pharma: pAUC expertise is no longer optional. Job postings for bioequivalence specialists now list it as a requirement in 87% of cases. Proficiency in Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM is expected. Training takes 3-6 months. The bar has been raised. If you’re a regulator: pAUC is here to stay. It’s not a replacement for Cmax and AUC-it’s a necessary addition. The future of bioequivalence isn’t about one metric. It’s about matching the right tool to the right drug.Partial AUC didn’t come to make things harder. It came to make them right.

What is partial AUC in bioequivalence?

Partial AUC (pAUC) measures drug exposure over a specific, clinically relevant time window-like the first 1-2 hours after dosing-rather than the entire concentration-time curve. It helps regulators compare how quickly a generic drug releases compared to the brand-name version, especially for extended-release or abuse-deterrent formulations where timing matters.

Why is pAUC better than total AUC for some drugs?

Total AUC tells you how much drug is absorbed overall, but not when. For drugs designed to release slowly-like extended-release painkillers-two products can have the same total AUC but different early release rates. One might flood the system too fast, raising overdose risk. pAUC focuses on that critical early phase, catching differences total AUC misses.

Which regulatory agencies require pAUC?

Both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) require pAUC for certain complex drug products. The FDA mandates it in over 127 product-specific guidances as of 2023, especially for abuse-deterrent opioids, extended-release CNS drugs, and mixed-mode formulations. The EMA introduced it in 2013 and has expanded its use since.

How is the time window for pAUC determined?

The cutoff time is based on clinically relevant pharmacodynamic effects, often tied to the reference product’s Tmax (time to peak concentration), or when drug levels reach 50% of Cmax. The FDA recommends linking the window to a known therapeutic or safety threshold. However, guidance varies by product, and only 42% of FDA product-specific guidances clearly define the method.

Does pAUC increase the cost of developing generics?

Yes. Because pAUC is more variable, studies often need larger sample sizes-sometimes 25-40% bigger than traditional studies. This can add hundreds of thousands of dollars to development costs. One company reported increasing their study size from 36 to 50 subjects, adding $350,000. Smaller firms often outsource pAUC analysis to specialized contract research organizations.

Is pAUC used for all generic drugs?

No. pAUC is only required for complex formulations where traditional metrics like Cmax and total AUC are insufficient. This includes extended-release drugs, abuse-deterrent opioids, and mixed-mode products. For simple immediate-release tablets, Cmax and AUC are still the standard.

Elliot Barrett

December 8, 2025 AT 20:17 PMLook, I don't care how fancy your metrics are-if a generic pill costs half as much and doesn't kill people, let it sell. pAUC is just another way for big pharma to delay generics and keep prices high.

Sabrina Thurn

December 9, 2025 AT 06:48 AMActually, the science behind pAUC is rock solid. For extended-release opioids, early exposure spikes are directly correlated with abuse potential and overdose risk. Traditional AUC can't capture that-your body doesn't care about total exposure, it cares about *when* the drug hits. pAUC forces generics to mimic the *pharmacokinetic profile*, not just the total dose. It's not about blocking competition-it's about preventing deaths.

Rich Paul

December 9, 2025 AT 06:53 AMBro, I work in bioequivalence and yeah pAUC is a nightmare. We had to run a 60-subject study for a metformin ER because the FDA wanted pAUC from 0-2h. We spent $500k. Meanwhile, the brand’s product has been on the market for 15 years and no one’s died. Why are we over-engineering this?

Maria Elisha

December 10, 2025 AT 06:44 AMI just take my meds. Why does this stuff matter? If it's cheaper and my doctor says it's fine, I'm good.

precious amzy

December 10, 2025 AT 12:19 PMOne might argue that the imposition of partial AUC as a regulatory criterion is not an advancement in pharmacological science, but rather a manifestation of epistemological overreach-an attempt to quantify the ineffable through statistical reductionism. The body is not a beaker, and time is not merely an axis on a graph. The therapeutic experience transcends pharmacokinetic curves, and to presume otherwise is to commit a category error of the highest order.

Tejas Bubane

December 10, 2025 AT 19:45 PMLet's be real, pAUC is just a fancy way to say 'we don't trust generic manufacturers'. The FDA's own data shows most generics are safe. This is just bureaucratic overkill dressed up as science. And don't get me started on the cost-small companies are getting crushed. This isn't safety, it's protectionism.

Noah Raines

December 12, 2025 AT 12:50 PMYeah but like, I’ve seen the data. That 22% early exposure difference? It’s real. I’ve read the case studies. People were getting dizzy, crashing, even overdosing because the generic hit too fast. pAUC isn’t perfect but it’s the only thing catching these killers before they hit shelves. 🤝

Suzanne Johnston

December 14, 2025 AT 03:00 AMIt's fascinating how regulatory science evolves in response to real-world harm. The shift from total AUC to pAUC mirrors a broader move in medicine-from population averages to patient-centered precision. We're no longer satisfied with 'close enough.' We demand functional equivalence. That’s progress, even if it's messy and expensive.

Delaine Kiara

December 15, 2025 AT 16:15 PMWait so you're telling me that a generic drug can have the exact same total drug in your system but still be dangerous because it hits too fast? That's wild. Like imagine if two cars had the same total fuel but one blasted off the line and the other crept. One could crash. That's pAUC. Mind blown. 🤯

Andrea Beilstein

December 15, 2025 AT 20:16 PMIt’s not about the math it’s about the silence between the peaks the pauses where the body breathes before the next surge the rhythm of healing not just the volume of intake we’ve forgotten that medicine is not a spreadsheet it’s a dance and pAUC is trying to hear the beat again

Simran Chettiar

December 16, 2025 AT 17:03 PMActually in my opinion the concept of partial AUC is quite profound because it reflects the dynamic nature of human physiology which cannot be captured by static parameters like total AUC. The body responds not to cumulative exposure but to temporal patterns and this is why the FDA and EMA are moving in this direction. It is not merely regulatory overreach but a philosophical shift towards chronopharmacology.

Ruth Witte

December 18, 2025 AT 02:38 AMYESSSS this is why I love science! 🙌 pAUC is literally saving lives by making sure generics don't sneak in like a drug dealer with a faster hit. Big Pharma hates it but patients win. Keep pushing the boundaries, regulators! 💪❤️

Sarah Gray

December 19, 2025 AT 08:47 AMAnyone who defends pAUC without acknowledging its statistical fragility and lack of universal standardization is either naive or complicit. The FDA’s inconsistent time windows are a regulatory nightmare. This isn’t precision-it’s arbitrary enforcement disguised as science. And you wonder why generics are vanishing from shelves?

William Umstattd

December 19, 2025 AT 22:46 PMLet me be perfectly clear: approving a generic drug that releases 50% of its dose in the first hour-when the brand releases only 30%-is not just a regulatory oversight. It is a moral failure. People die from opioid overdoses. Children lose parents. Families are shattered. If pAUC prevents even one of those tragedies, then the $350,000 cost is not an expense-it is a redemption. The FDA is not being bureaucratic. It is being responsible. And those who oppose it are not advocates for affordability-they are apologists for risk.