Gallstone Pancreatitis Risk Calculator

Select the risk factors you have:

Select the type of gallstone you have or are likely to develop:

Your Risk Assessment

Ever wondered why a trouble in the gallbladder can knock your pancreas off balance? The link between gallstone pancreatitis is more common than you think, and knowing the connection can spare you a lot of pain.

Quick Facts

- Gallstones are solid particles that form in the gallbladder, often made of cholesterol or bilirubin.

- When a stone blocks the bile duct, it can back‑up digestive juices into the pancreas, causing pancreatitis.

- Typical symptoms include severe upper‑abdominal pain, nausea, and fever.

- Diagnosis relies on blood tests, ultrasound, and sometimes CT or MRI scans.

- Treatment ranges from observation to endoscopic removal (ERCP) or surgery (cholecystectomy).

What Are Gallstones?

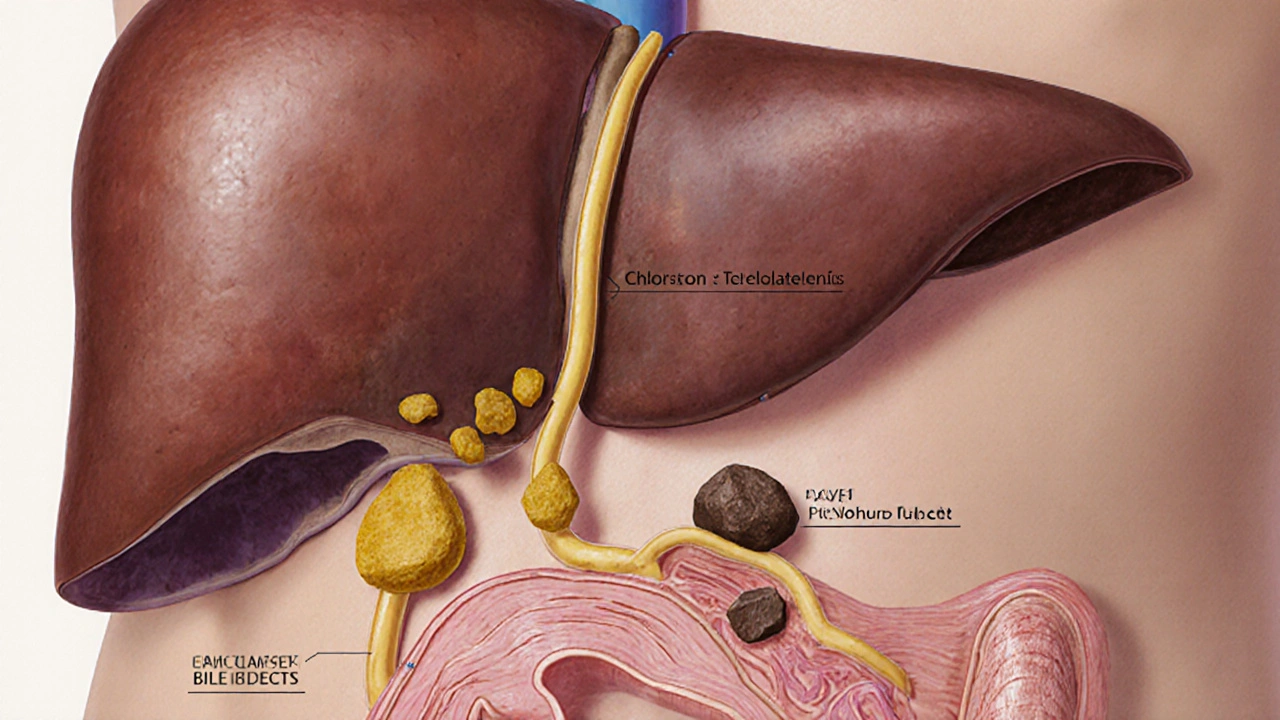

Gallstones are solid deposits of cholesterol, bilirubin or mixed substances that form in the gallbladder. Most people don’t notice them until they cause a problem. The two main types are:

- Cholesterol stones - usually yellow, composed mainly of hardened cholesterol.

- Pigment stones - darker, made from bilirubin, often linked to liver disease or hemolysis.

Risk factors include a high‑fat diet, obesity, rapid weight loss, genetics, and certain medical conditions like diabetes.

How Gallstones Trigger Pancreatitis

Think of the digestive system as a plumbing network. The gallbladder stores bile, which travels through the common bile duct to the small intestine. The pancreas releases digestive enzymes into the same duct system via the pancreatic duct. When a stone slides down and lodges at the junction where the bile and pancreatic ducts meet (the ampulla of Vater), it creates a traffic jam.

This blockage forces pancreatic enzymes to back‑up into the pancreas itself, where they start digesting the organ’s own tissue - that’s acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas, often marked by sudden, severe abdominal pain and elevated enzyme levels. When the cause is a gallstone, clinicians call it “gallstone pancreatitis.” Studies from the American College of Gastroenterology show that gallstones account for about 35‑40% of all acute pancreatitis cases in the United States.

Symptoms to Watch For

If a stone is sitting in the bile duct, you might feel:

- Intense pain in the upper right or middle abdomen that radiates to the back.

- Nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite.

- Fever or chills - a sign of possible infection.

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes) if the stone also blocks bile flow.

- Elevated blood levels of lipase or amylase, enzymes that spike during pancreatitis.

These symptoms often appear suddenly and can last from a few hours to several days. If the pain is severe and doesn’t improve with over‑the‑counter pain relievers, it’s time to seek medical care.

How Doctors Diagnose the Problem

Diagnosis is a step‑by‑step process:

- Blood tests: High lipase or amylase confirms pancreatitis; liver function tests may show bile blockage.

- Imaging: An abdominal ultrasound is the first line to spot gallstones. If the stone is not seen, a CT scan or MRI can reveal inflammation in the pancreas.

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): ERCP is a minimally invasive procedure that uses an endoscope and contrast dye to visualize and sometimes remove stones from the bile and pancreatic ducts. It serves both diagnostic and therapeutic roles.

In most hospitals, the combination of elevated enzymes and an ultrasound‑confirmed stone is enough to start treatment without waiting for more advanced imaging.

Treatment Options

Management depends on severity:

- Mild cases: Hospital admission for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The stone may pass on its own.

- Moderate to severe cases: ERCP to extract the stone promptly, preventing ongoing pancreatic injury.

- Definitive solution: Cholecystectomy is surgical removal of the gallbladder, usually done laparoscopically, which eliminates the source of future stones. It’s recommended within a few weeks of the initial episode.

If infection occurs, antibiotics are added. In rare cases of necrotizing pancreatitis, intensive care and possibly surgical debridement are required.

Prevention & Lifestyle Tweaks

Even after the gallbladder is gone, certain habits can help keep the pancreas happy:

- Maintain a healthy weight - aim for a gradual loss of no more than 1‑2 pounds per week.

- Follow a low‑fat, high‑fiber diet: fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins.

- Limit sugary drinks and refined carbs, which can raise cholesterol levels that contribute to stone formation.

- Stay hydrated - bile becomes less concentrated when you drink enough water.

- Discuss any medication that might increase stone risk (e.g., certain hormonal therapies) with your doctor.

Regular check‑ups are key, especially if you have a family history of gallstones or pancreatitis.

When to Call Emergency Services

If you notice any of the following, treat it like a medical emergency:

- Sudden, unrelenting abdominal pain that doesn’t improve after an hour.

- High fever (>101°F / 38.3°C) or chills.

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes.

- Vomiting that contains blood or looks like coffee grounds.

Prompt treatment can prevent complications such as infection, organ failure, or chronic pancreatitis.

Comparison of Gallstone Types and Typical Pancreatitis Triggers

| Stone Type | Primary Composition | Typical Risk Factors | Likelihood of Triggering Pancreatitis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | Hardened cholesterol | Obesity, high‑fat diet, rapid weight loss | High - 40% of stones cause blockage |

| Pigment | Bilirubin | Liver disease, hemolysis, chronic infections | Moderate - often cause bile duct blockage |

| Mixed | Both cholesterol and bilirubin | Combination of above risk factors | Variable - depends on size and location |

Take‑Home Checklist

- If you have known gallstones, watch for sudden upper‑abdomen pain.

- Get an ultrasound when pain spikes - it’s the quickest way to spot a stone.

- Ask about ERCP if the stone is stuck; it can relieve the blockage without open surgery.

- Plan for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy after the acute episode to prevent recurrence.

- Adopt a low‑fat, high‑fiber diet and keep active to lower future stone risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can gallstones cause chronic pancreatitis?

Repeated episodes of gallstone blockage can lead to ongoing inflammation, which over time may evolve into chronic pancreatitis. Removing the gallbladder after the first severe attack reduces this risk.

Is surgery always required after gallstone pancreatitis?

Not always. If the stone passes spontaneously and there are no further episodes, doctors might monitor the patient. However, guidelines suggest cholecystectomy within 6‑8 weeks to prevent a repeat event.

What diet should I follow after a gallbladder removal?

Start with low‑fat, easily digestible foods for the first few weeks (broths, steamed veggies, lean protein). Gradually re‑introduce healthy fats like olive oil and avocado, but keep total fat under 30% of daily calories.

How is gallstone pancreatitis different from alcohol‑induced pancreatitis?

Both cause inflammation, but gallstone pancreatitis often presents with jaundice and a sudden rise in liver enzymes, whereas alcohol‑related cases show a history of heavy drinking and usually lack bile duct blockage.

Can I take herbal remedies to dissolve gallstones?

No reliable scientific evidence supports natural supplements for dissolving stones. Most effective non‑surgical options are ERCP or lithotripsy, and these should be performed by a gastroenterologist.

Angie Wallace

October 3, 2025 AT 14:13 PMGreat breakdown, this really helps you see the connection between gallstones and pancreas issues. Keeping an eye on diet and weight can make a big difference in preventing the whole cascade.

Doris Montgomery

October 11, 2025 AT 19:33 PMHonestly, the article feels like a rehash of anything you can find on the web. It throws a lot of facts at you without any real insight or fresh perspective.

Nick Gulliver

October 20, 2025 AT 00:53 AMAll this medical jargon is just a way to scare people.

Sadie Viner

October 28, 2025 AT 05:13 AMThank you for the thorough overview. The way you delineated cholesterol and pigment stones, then linked each to the mechanisms of pancreatic injury, was particularly enlightening. I also appreciated the clear checklist at the end; it provides a practical take‑away for anyone dealing with this condition. Your inclusion of lifestyle modifications alongside medical interventions strikes a perfect balance between prevention and treatment.

Kristen Moss

November 5, 2025 AT 10:33 AMDude, if you’re not cutting the fat ASAP you’re just asking for a stone to block your ducts. Get on it.

Rachael Tanner

November 13, 2025 AT 15:53 PMDid you know that the majority of gallstone‑related pancreatitis cases occur in patients with a BMI over 30? That’s a striking statistic that underscores the obesity‑pancreatitis axis. Also, the article could have highlighted the role of ursodeoxycholic acid as a non‑surgical option for dissolving cholesterol stones, which some clinicians still consider.

Debra Laurence-Perras

November 21, 2025 AT 21:13 PMLet’s keep the conversation respectful – it’s important to share accurate info without shaming anyone for their health journey. Remember, every step toward a balanced diet and regular activity is a win.

dAISY foto

November 30, 2025 AT 02:33 AMWhoa! This read felt like a rollercoaster of facts and life‑hacks. I’m vibing with the idea that staying hydrated can actually thin out bile and keep those nasty stones at bay. Also, kudos for dropping the reminder that even after gallbladder removal, you still need to watch your fats – the pancreas still feels the love (or lack thereof) from your diet.

Ian Howard

December 8, 2025 AT 07:53 AMThe piece nails the clinical pathway from symptom onset to ERCP. It’s crucial for patients to understand that early imaging, especially a fast ultrasound, can spare them a lot of pain. I’d add that a serum calcium check can sometimes reveal hypercalcemia as an underlying stone‑forming culprit.

Chelsea Wilmer

December 16, 2025 AT 13:13 PMWhen we contemplate the intricate symbiosis between the biliary and pancreatic ducts, we must first acknowledge the profound evolutionary orchestration that permits the dual exocrine secretions to converge at the ampulla of Vater, a convergence that, while a marvel of physiological engineering, also becomes a pivotal point of vulnerability when confronted with crystalline intruders such as gallstones. The article admirably charts the cascade from lithogenic milieus – high‑fat diets, rapid adipose depletion, and genetic predispositions – to the mechanical obstruction that precipitates a retrograde surge of pancreatic enzymes, instigating autodigestion and, consequently, acute pancreatitis. It is noteworthy that cholesterol‑rich stones, owing to their larger size and propensity for impaction, dominate the statistical landscape, accounting for roughly 40 % of obstruction‑related pancreatitis episodes, a figure corroborated by multiple epidemiological surveys across Western cohorts. Moreover, pigment stones, though less prevalent, underscore the interplay between hemolytic disorders and bilirubin supersaturation, further diversifying the stone composition spectrum.

From a diagnostic viewpoint, the triad of elevated serum lipase, ultrasonographic detection of echogenic foci within the gallbladder, and corroborative impaired liver function tests should catalyze immediate therapeutic deliberation. While conservative management – intravenous hydration, analgesia, and vigilant monitoring – suffices for mild presentations, the urgency of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) cannot be overstated in moderate to severe cases, as it offers both diagnostic clarity and therapeutic extraction of the offending calculi. This dual capacity not only alleviates ductal obstruction but also mitigates ongoing pancreatic insult, thereby curbing the trajectory toward necrotizing pancreatitis and its attendant morbidities.

Equally imperative is the recognition that definitive prophylaxis resides in cholecystectomy, ideally scheduled within six to eight weeks post‑episode to forestall recurrence. The laparoscopic approach has become the gold standard, conferring minimal invasiveness, reduced postoperative discomfort, and expedited convalescence. Nevertheless, patient‑specific factors such as comorbid cardiopulmonary disease may necessitate alternative strategies, including percutaneous cholecystostomy or even conservative observation in select scenarios where surgical risk outweighs benefit.

Preventive counsel extends beyond operative measures. A dietary framework enriched with soluble fiber, low in saturated fats, and replete with antioxidant‑laden produce can attenuate cholesterol supersaturation in bile, thereby diminishing lithogenic potential. Hydration status, too, proves pivotal; adequate fluid intake ensures bile remains sufficiently dilute to avert crystallization. Regular aerobic activity, calibrated to promote gradual weight loss, circumvents the rapid adipose turnover that paradoxically precipitates stone formation.

In summation, the nexus between gallstones and pancreatitis epitomizes a paradigmatic illustration of how anatomical proximity can translate into pathological interdependence. Recognizing early clinical hallmarks, deploying prompt imaging, and instituting timely endoscopic or surgical intervention collectively constitute the cornerstone of optimal patient outcomes. By integrating lifestyle modification with evidence‑based medical practice, clinicians can not only treat acute episodes but also empower patients to avert future biliary‑pancreatic crises.

David Stout

December 24, 2025 AT 18:33 PMI appreciate the balanced tone here – you’ve laid out the facts without sounding alarmist, and the step‑by‑step guide makes it easy for anyone to follow.

Pooja Arya

January 1, 2026 AT 23:53 PMFrom a moral standpoint, we should strive to educate people about the lifestyle factors that lead to gallstones, rather than simply treating the symptom after it’s too late. Knowledge is empowerment.

Sam Franza

January 10, 2026 AT 05:13 AMClear and concise – the minimal punctuation helps the key points stand out without unnecessary clutter.

Raja Asif

January 18, 2026 AT 10:33 AMThis is why we need tougher health policies; if people keep eating junk, we’ll keep seeing these preventable cases of gallstone pancreatitis.

Matthew Tedder

January 26, 2026 AT 15:53 PMIt’s helpful to see the emphasis on early detection and the supportive tone around lifestyle changes. That can make a real difference for patients.

Cynthia Sanford

February 3, 2026 AT 21:13 PMAwesome article – love the practical checklist. Gonna try cutting down on fried stuff ASAP.

Yassin Hammachi

February 12, 2026 AT 02:33 AMThe balanced perspective presented here respects both medical intervention and personal responsibility, which is essential for sustainable health outcomes.

Michael Wall

February 20, 2026 AT 07:53 AMHonestly, the article could have been simpler. Some of the terms are over the top for a general audience.